When Tories believed in Europe

Britain has left the European Union. The fight is over.

In truth, the fight ended before the referendum in June 2016. Years before. For decades, British governments believed in membership of the EU but did nothing to encourage popular support for it. The first instinct of struggling governments – such as John Major’s in the 1990s – was to pick a fight with Brussels. The creators of Yes Minister instinctively understood this – Jim Hacker became PM in that classic comedy series after leading a campaign against the Euro sausage. An earlier episode railed against European computer standards.

So I was in no doubt in 2016 that the referendum could well be lost. When our European chief executive asked me that February what the outcome would be, I said I feared the UK would vote to leave.

Yet I fervently hoped it wouldn’t. Days before, I spent time in Luxembourg with colleagues from all the major EU nations. Like many, I work with people from a host of nations, and have learned so much from this multi-nation and multi-cultural interchange. It feels the most natural thing in the world.

It wasn’t always like this. Growing up in the 1970s, as Britain joined the then European Economic Community, I sympathised with the view that we were abandoning our Commonwealth cousins by joining the EEC. Peter Hennessy’s superb history of Britain in the early 1960s, Winds of Change, recounts the agonies of Harold Macmillan’s bid to join, rebuffed by General de Gaulle. (On reflection, perhaps the general’s non was right.) The epic waste of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) offended every instinct – as taxpayers spent billions buying unwanted cheese and milk, enriching French farmers. But we were late to the party, and couldn’t reasonably complain that the kitty had already been spent. As an 11 year old hostile to the EEC during the 1975 referendum, I proudly taped the leave leaflet to the inside of my desk at Lakeside School in Cardiff. (My friends were far more interested in whether Bay City Rollers would get to Number 1 in the charts.)

I spent a year studying European Communities law at university in 1983, which wasn’t my most inspiring subject. (But it came in useful years later.) In time, I came to see Britain’s membership of the EU as valuable for us and our continental friends. The UK played an increasingly influential role in Europe, helping the continent chart a path that blended citizens’ rights with encouraging economic development. And we won critical concessions, such as avoiding membership of the ill-conceived euro. (The common currency has arguably been better news for British citizens travelling across the EU than it has been for many people in the euro-zone, with its disastrous impact on the economies of so many nations.)

I voted remain. I condemned the lies of the leave campaign, and the appalling way Corbyn’s Labour Party failed to campaign wholeheartedly for Britain to remain in the referendum. It was a tragedy that Labour chose Corbyn as leader just as the battle for Britain’s European future began. But as Boris Johnson won his historic election victory in December 2019, I felt curious relief. I didn’t vote for this deeply flawed politician. But the result settled the biggest issue facing Britain.

How will this end? None of us knows. We can but hope that Johnson raises his game, and becomes a man of destiny. If the UK is to survive and flourish, he needs to play a blinder. He needs to create a new sense of national unity that starts to heal the schism with Scotland, and heals the rest of the nation. Britain is certainly big enough to do well outside the EU, but our politicians – of all parties – need to do far better than their dismal performance over the past five years.

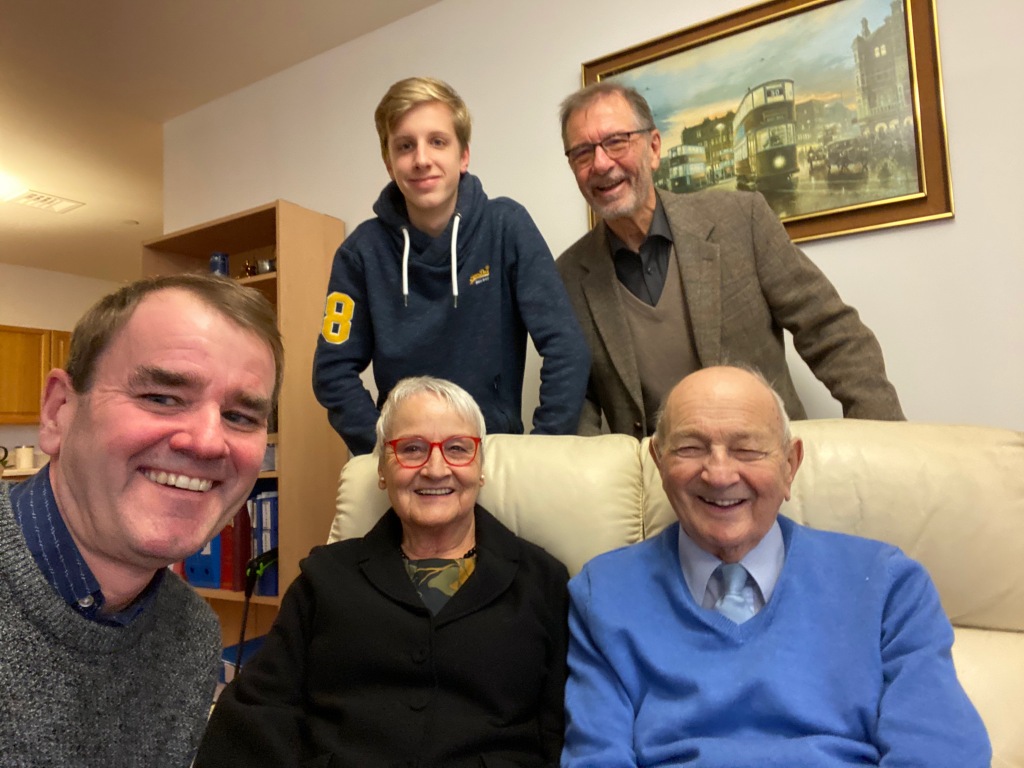

We are still Europeans. We travel far more than our grandparents did. As Britain’s EU odyssey ends, I recall and cherish our family friendships across our continent. In the 1950s and 1960s, Mum and Dad met Charles, Rosel, Werner, Sabine, Uschi, Helmut and others. Those friendships were born in the town twinnings between Wales and Germany. It is so moving to reflect that our countries were at war less than 15 years earlier. But there was a compelling wish to build bridges across the years. One of my favourite moments of 2019 was meeting Werner, Sabine and their grandson in Cardiff and reminiscing about shared memories and values We mourned Britain’s departure from the EU, but agreed that friendships are deeper than political structures. Britain remains at the heart of Europe.

Postscript: I wrote the article below in 1995 after a lively dinner discussion with the then editor of The Independent. It reads like an elegy for a lost world. But pleasingly Wales now has the Senedd that the article envisaged 25 years ago.

Europe – a dangerous obsession

Rob Skinner, March 1995

British democracy is at crisis point. Not just because fifteen years without a change of government has left the nation restless for change. Not even as a result of former ministers making sleazy, easy money in a privatised quangocracy.

No, this crisis is a case of obsession. The subject of this obsessions is Europe, the perpetrators politicians and the media alike. This single topic dominates news bulletins, current affairs programmes and the leader columns of the national press. Yet it utterly fails to stimulate the nation.

The Euro-debate is almost entirely the preserve of the political professionals. Europe and its future currency is for most of the British people the non-issue of the decade. It rarely if ever puts in an appearance in public bars and at dinner party tables.

If the loudly debated referendum on the single currency took place tomorrow, Britain’s polling stations would almost certainly be lonely places as the electorate used their time to fulfil other, more pressing needs.

The media star a heavy responsibility for this sorry saga. Radio 4’s Today programme, in particular, has been dominated by Euro-obsessed talking heads for what seems an eternity, while the surfeit of Sunday political punditry on British television finds Europe a lazily easy choice for discussion.

Yet the obsession simply confirms what everyone outside Westminster’s cloistered circles has long suspected: that politicians are hopelessly out of touch with the real world, and incapable of tackling the issues that their constituents care and worry about.

Most people see Europe as a distraction. They long for a government and opposition that tackle the real issues of the day, such as unemployment, crime, rising taxes and the sense that Britain has become a less caring, more ugly society. For many, the great fear is not the loss of the UK’s economic sovereignty but the loss of something much nearer to home – their jobs.

None of these issues is being tackled. Instead, a sterile, futile debate dominates, which looks for all the world like an endless battle between two foolish lovers. The weakest, most enfeebled government in living memory seeks to impose the very thing it lacks – authority – on the country. A cynicism fired by years of misrule is now raging out of control, threatening Britain’s self confidence as a nation.

As a Welshman, I see Europe as an opportunity, not a threat. I believe in a Europe of many countries and cultures – not just a Europe of nation states. The doomed debate that has riven the Conservatives is very English rather than British. It speaks eloquently of a nation uncertain of itself, suspicious of outsiders and nervous of its smaller neighbours within the United Kingdom.

This is high irony. How could the dominant tribe in the British Isles, the English, have become so fearful, so lacking in vision of confidence that they have largely destroyed Britain’s standing on its own continent?

The crying shame is that Europe is important. There must be a proper debate about Britain’s future. We should be looking for ways to put right the failings of the democratic process in the European Union and within these islands. And we must be open and humble enough, for once, to recognise that the United Kingdom might profitably learn from democratic experiences beyond these shores.

John Major has sought sanctuary behind an ugly word – subsidiarity. Yet this strange and unfriendly term signals the way to make Europe and Britain more democratic. The principle is that decisions should be made as locally as possible. Yet in the UK, under John Major’s desperate leadership, the concept has been hijacked, and given a new, sinister meaning. That mother – the Mother of Parliaments – knows best. Yet who truly places trust in the traditional Westminster system in 1995?

Subsidiarity needs a new, more attractive name. The Welsh word agosrwydd means nearness, and has been suggested by David Morris MEP and Martin Caton as a far better epithet.*

If the English aren’t ready to accept a Welsh word for what might be the most important democratic principle of the dying years of the millennium, then nearness will serve just as well. It is a compelling sentiment, an idea whose time has come. The European Union is here to stay, and Britain’s future is inextricably linked to it. For non-state regions and countries like Wales, Scotland, Baden Würtemberg and Catalunya, being part of a wider family is a historic development that arguably makes the break up of nation states like the UK less likely. But it is only less likely if the nearness principle puts greater power in the hands of regional governments such as a Welsh Senedd.

John Major talks of a triple lock within the burgeoning Northern Ireland peace process. In a wider concept, three links also hold the key to unlocking the eternal dilemma that has dogged Britain for a quarter of a century: regional identity, our British identity and the European dimension. Only by creating harmony between all three, and recognising their legitimacy, will we ever escape this constitutional conundrum.

In this anniversary year [1995], of all years, we must look back to 1945. Not only to commemorate the huge sacrifices made to secure our generation’s freedom and future. But just as nobly to recall how the European ideal was born, in the ruins of a continent that had allowed evil and hatred to carry all before it.

After Warsaw, Aschwitz and Dresden, reconciliation might have been expected to have taken decades to bear fruit. Yet amidst the tragedies of an unimaginable numbers of lives, the determination to forge a different Europe was born. Since those dawning days, the idea of Britain and Germany taking up arms against each other, or Belgium and France being overrun by a continental army, has become inconceivable.

Now the challenge for Britain’s politicians is to shake off their obsession and start treating Europe as something that is part of everyone’s lives. Votes can only be lost over this issue, not won, and it is time for Eurosceptic and Europhile alike to recognise the basic truth. The year of the last great second world war anniversaries would be an appropriate time for Britain belatedly to throw away the empty rhetoric and start to build a future for itself.

* A Europe of the Peoples – the European Union and a Welsh Parliament’ – ed John Osmond, Gomer Press 1994