This is the third in a series of posts about my training and preparation for the 1530km London Edinburgh London audax event in August 2025. The series was inspired by LEL supremo Danial Webb asking if anyone was planning to post about their training and preparation for the event. Read part one here and part 2 here.

They say we learn far more from our failures than our successes. If so, my experience on last weekend’s Bryan Chapman Memorial 600km audax ride should really help me on London Edinburgh London in August.

I’ve written a blow-by-blow account of the ride here, so head over there for the gory details. Or you can watch my five minute highlights video:

Here, I’ll share what I learned on the Bryan Chapman. Let’s start on a positive note: what went well.

The right bike

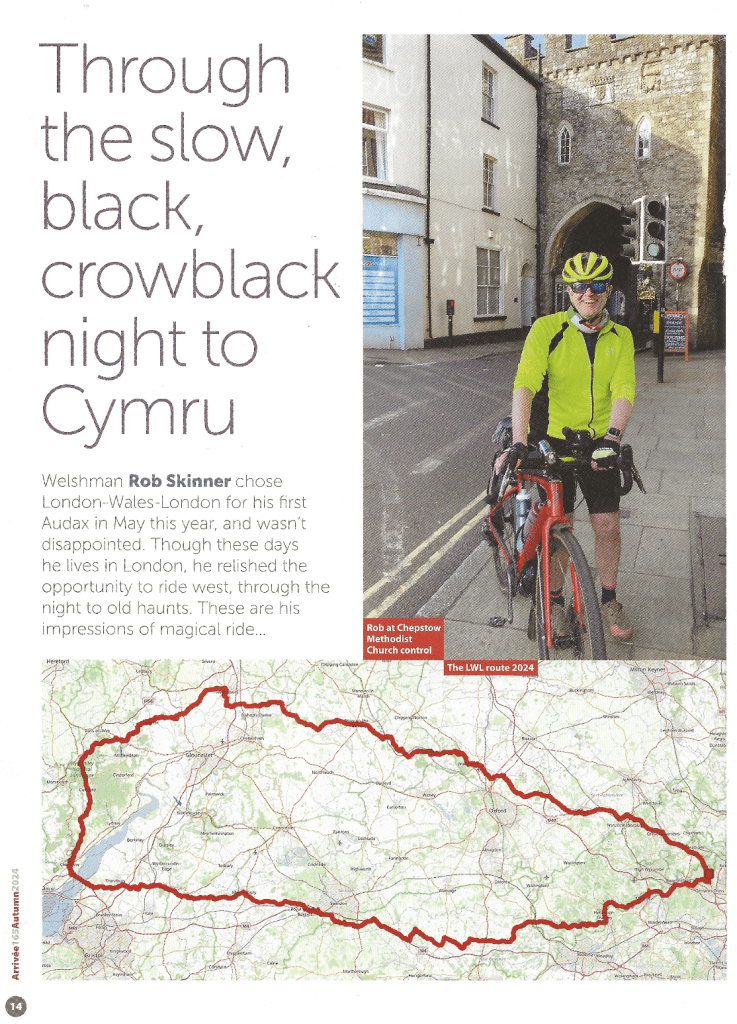

Should you ride your fastest or your most robust bike on a big audax event? I chose my Specialized Diverge gravel bike. It’s seen me through countless adventures including two editions of London Wales London. It’s not my lightest bike, but its 38mm tyres give me such reassurance, especially when hitting a pothole at speed in the middle of the night.

My Restrap custom frame bag was so useful

One of the disadvantages of riding a small frame bike – in my case 54mm – is that only the smallest frame bags fit. On a 600km or longer audax event that is a pain. But I noticed that Restrap offer a custom frame bag for a very reasonable £119.99. I sent off for the design pack, which helps you work out the dimensions, and where the various straps should go.

My wife Karen and I carefully followed the instructions to design my custom bag, and I placed my order. At first I was afraid the bag wouldn’t arrive in time given the stated lead times, but the Restrap team was brilliant, and I received the bag a week before the Bryan Chapman. It fitted perfectly, and was a huge help on the ride.

Cutting the ride short: the right decision

A few weeks ago, endurance cyclist Emily Chappell invited advice on her Substack post about long-distance cycling. I gave a few tips, including not giving up cheaply when you’re at your lowest ebb. Eat, sleep, and reflect.

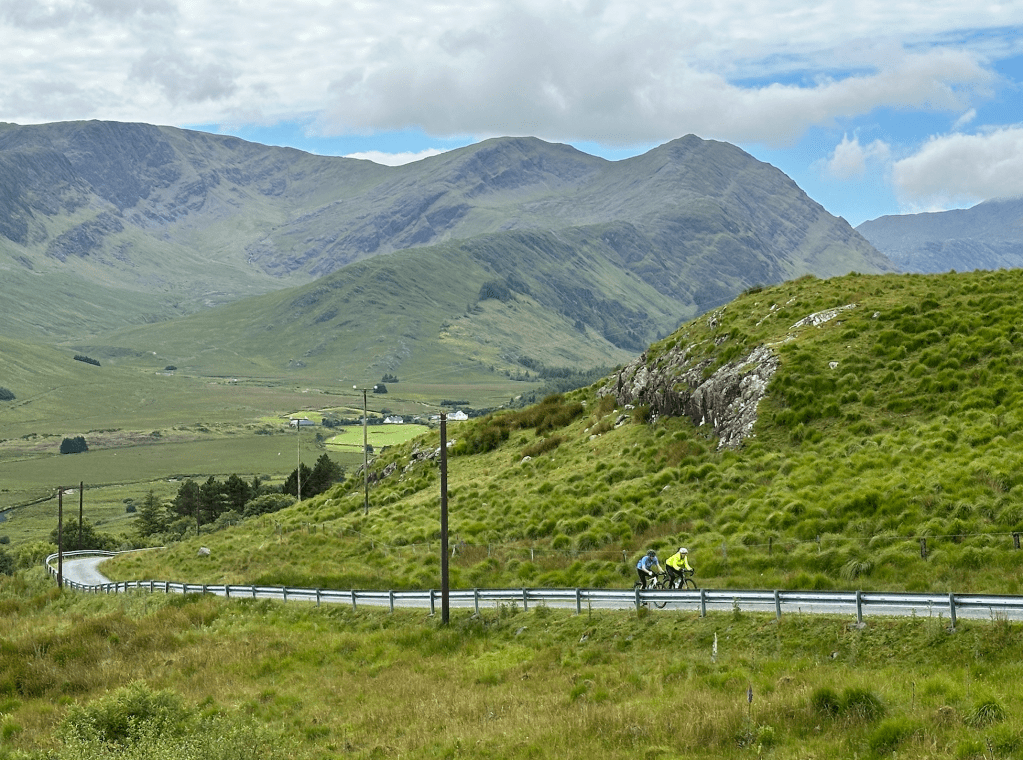

So it was ironic that I decided to cut short my Bryan Chapman route, going straight from the Dolgellau control at Kings Youth Hostel to the sleep stop at Aberdyfi. I made the decision after going miles off route because my Garmin led me onto the southbound track when I was still heading north. As a result, I had a massive, additional pass to climb, and lost a huge chunk of time.

I had already made the decision before Kings, and it was undoubtedly the right one. I could enjoy a reviving stay at the control, relish the coastal ride to Aberdyfi, and be in far better condition for the remaining 210km in the morning. Best of all, I was at peace with the failure to get to Menai Bridge. I could do my Welsh end to end another time.

My near midnight finish on the second day shows how right I was.

Taking spare SRAM batteries was vital

If you ride electronic gears, you have to be ready to replace or charge batteries on the road. SRAM eTap batteries theoretically last up to 1,000km, at least when new. I had to pop in a spare one after around 375km. Those constant gear changes on the very hilly Bryan Chapman drained the battery far sooner than I expected. But I was prepared.

The volunteers were amazing

As I spent time recovering at Aberdyfi, I was struck once again by the critical role volunteers play in audax events. One female helper seemed to be ever present – there when I went to sleep past midnight, and again when I went for breakfast just after 6am. She was constantly replenishing supplies and helping weary riders. To her and every other volunteer, and organiser Will Pomeroy: thank you!

So… the lessons I need to learn from

Make your own decisions

I was seriously underfuelled at times on the Bryan Chapman. Twice I allowed myself to be led by other people’s examples. After 74km at the first control, I ordered a small breakfast, as others had done, but it wasn’t enough. Later, after seeing Bryan Chapman riders eating at a bakery I did the same, even after finding the choice very limited.

On an audax like Bryan Chapman, you have to find your own food except at a small number of controls. You really have to make smart choices. I didn’t.

London Edinburgh London is very different, with food on offer at controls throughout the route. (Although judging from accounts of previous editions supplies may be limited if you arrive at a very busy time.) If you feel lethargic, don’t miss the chance to eat proper food – bars and gels can get you only so far.

Don’t trust your Garmin

My great mistake on the Bryan Chapman was to trust my Garmin’s directions. When it told me to turn off the main road between Machynlleth and Dolgellau I obeyed, and went miles off route, requiring an extra, very big climb. I didn’t realise it was sending me on the following day’s ride. Organiser Will Pomeroy had provided control-to-control GPS files. Had I used those, rather than the complete route version, I’d have been OK. Something to ponder with London Edinburgh London, whose northbound and southbound routes also cross.

You may be slower than you think

I deliberately didn’t try to estimate when I’d reach the various controls on Bryan Chapman. I knew how hilly the route was. Yet on the second day, I still under estimated how slow I’d be. The lack of sleep, and eating too little, had a big impact. I should have left Aberdyfi 90 minutes earlier at least.

Prepare to sleep

I’d brought a sleeping bag liner as I’d heard that the blankets provided at the Bryan Chapman sleep stop could be scratchy. I could have done with ear plugs to block out the constant noise of people coming and going, accompanied by their phone wake up alarms. One for the kit list for London Edinburgh London.

At a low point on a quiet mountain road, I enjoyed a power nap on a grassy verge beside the road. It revived my spirits. On London Edinburgh London, I’ll take the opportunity for a half hour nap at controls during the day if I need to.

Final thoughts

I booked to enter the Bryan Chapman as a test of my readiness for London Edinburgh. I’m glad I did. While I failed to complete the full 600km, I did ride further than I’d ever done before in two days. But I need to learn from my mistakes, and continue to build my endurance fitness. I’m starting a bike ride through France from the English Channel to the Mediterranean tomorrow, which should help!

UPDATE: read the next post in my series about preparing and training for London Edinburgh London: joining the LEL volunteers to create over 2,400 rider starter packs.