James Callaghan, who died 20 years ago this week, might have been Britain’s most forgotten postwar prime minister had it not been for the winter of discontent. The strike-dominated final months of his premiership, when bodies went unburied and rubbish piled up in the streets, ensured a convincing victory for Margaret Thatcher in the 1979 general election.

Yet Callaghan was a more successful prime ministers than critics allow, especially given his terrible inheritance. When he took over after Harold Wilson’s surprise resignation in 1976, inflation was running at almost 19 percent a year. He inherited a wafer-thin majority, which had disappeared within a year. The trade unions were pushing for ever-bigger pay increases to offset inflation, but which inevitably pushed prices higher still.

Callaghan was unfazed by it all – at least until the final, bleak winter. A man who had fought in the second world war, and been through a different kind of fire as chancellor, home secretary and foreign secretary, calmly faced whatever crisis came his way. This was one reason why he was more popular as PM than his party or his Conservative rival Margaret Thatcher. In troubled times, Sunny Jim was a reassuring captain even as the ship was at risk of sinking.

He led his cabinet with a rare skill. Those were the days of political ‘big beasts’ – Denis Healey, Tony Benn, Michael Foot, Roy Jenkins and Anthony Crossland were just some of the big names in his cabinet. (He sent the formidable Barbara Castle, once tipped to be Britain’s first woman PM, to the back benches.) Callaghan’s achievement in getting the Cabinet to agree to dramatic public spending cuts in the face of the sterling crisis months after he took over was striking. He used his diplomatic skills to get American president Ford to put pressure on the IMF to grant Britain a loan. And he called nine lengthy cabinet meetings to discuss and agree the cuts required by the International Monetary Fund for it to grant that loan. The born-again left winger Tony Benn pushed hard for an alternative economic policy based on import controls, rather than public spending cuts. Callaghan showed saintly patience in handling Benn, who in turn praised his leader as a much better PM than Wilson.

The historian Dominic Sandbrook has described Callaghan’s handling of the 1976 crisis as ‘a remarkable achievement’. Writing in Seasons in the Sun, his history of Britain 1974-76, Sandbrook noted that the new PM had worked miracles to mollify the markets, strike a deal with the IMF and keep the government united, despite the inescapable fact that having to ask for a loan was humiliating for Britain. Yet the great irony is that the crisis was based on typically flawed Treasury figures. Instead of borrowing £11 billion a year, Britain was actually borrowing £8.5 billion. Chancellor Denis Healey only needed half the IMF loan, and repaid it far sooner than anyone expected. But history had been made regardless: he and his PM had ended Britain’s postwar Keynesian economic policy, adopting monetarism three years before the arch monetarist Margaret Thatcher came to power.

By 1978, the dark economic clouds seem to be lifting. Inflation was down to 8 percent from the 1975 high of 24 percent; Britain was starting to enjoy the North Sea oil bonanza; and Chase Manhattan’s European economist proclaimed that ‘the outlook for Britain is better than at any time in the postwar years’. Consumers were buying new cars, fridges and washing machines. As a later generation would say, the feel good factor was returning. This seemed like the perfect time to call an election, and secure a Labour government into the 1980s.

Most people – including his advisers – thought Sunny Jim would go to the country. The Times reported on 3 September 1978 that an election was likely to be announced within a week. Union leaders urged an election, and so avoid a winter wage explosion. (How right they were…) Just two days after that Times story, Callaghan teased the TUC conference about calling an election, even singing an old song, Waiting at the Church, about a bridesmaid being jilted at the altar by her fiancé because his wife wouldn’t let him marry her. (He attributed the song to the music hall singer Marie Lloyd, but it was actually sung by her less well known rival Vesta Victoria.)

He ended by saying that he had ‘promised nobody that I shall be at the altar in October, Nobody at all.’ If he intended to end speculation about an election, his mock-serious approach failed completely. Callaghan broadcast to the nation saying there would be no early election.

Many cabinet ministers and advisers were shocked and disappointed. With hindsight – notably the searing memories of the winter of discontent – his decision to soldier on looks like a disastrous blunder. Yet that ignores a fundamental truth. Prime ministers rarely call elections before they need to unless they are sure they will win. With the exception of Rishi Sunak in 2024, they don’t want to lose their unique status as leader of the nation prematurely. Callaghan was a cautious politician and the polls in the late summer of 1978 suggested a hung parliament, with neither Labour or the Conservatives with a majority. The only certainty about his decision is that he condemned Labour to a heavier defeat that would have happened in October 1978, rather than turning victory into defeat. His great mistake was to allow the speculation to run out of control. It was a mistake repeated by Gordon Brown in 2007.

The real Jim Callaghan

The ignominious end to his premiership should not obscure Callaghan’s remarkable story in rising to the top. Like so many British prime ministers, James lost his father at a young age, nine. His mother got by on a naval widow’s pension granted by the first Labour government in 1924, but it was not enough to pay for him to go to university. He felt his lack of a degree keenly, although he made fun of it when interviewed by the BBC’s Desert Island Discs in 1987:

‘If people say I’m not clever at all, I’m quite prepared to accept that, except that I became prime minister and they didn’t, all these clever people!’

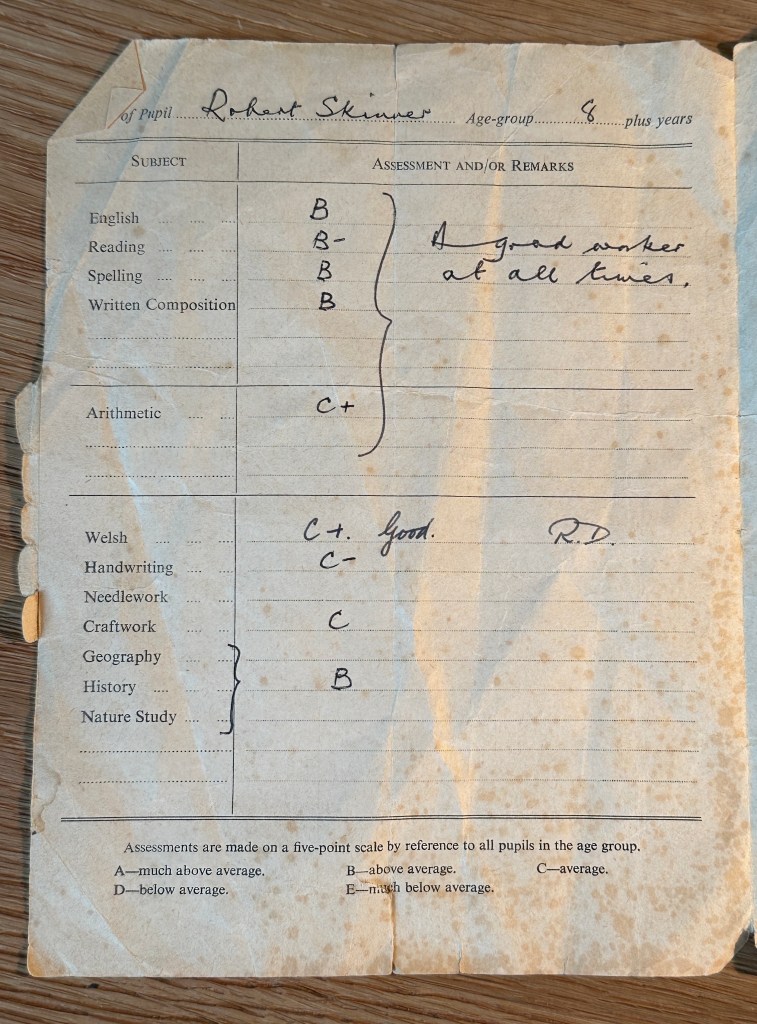

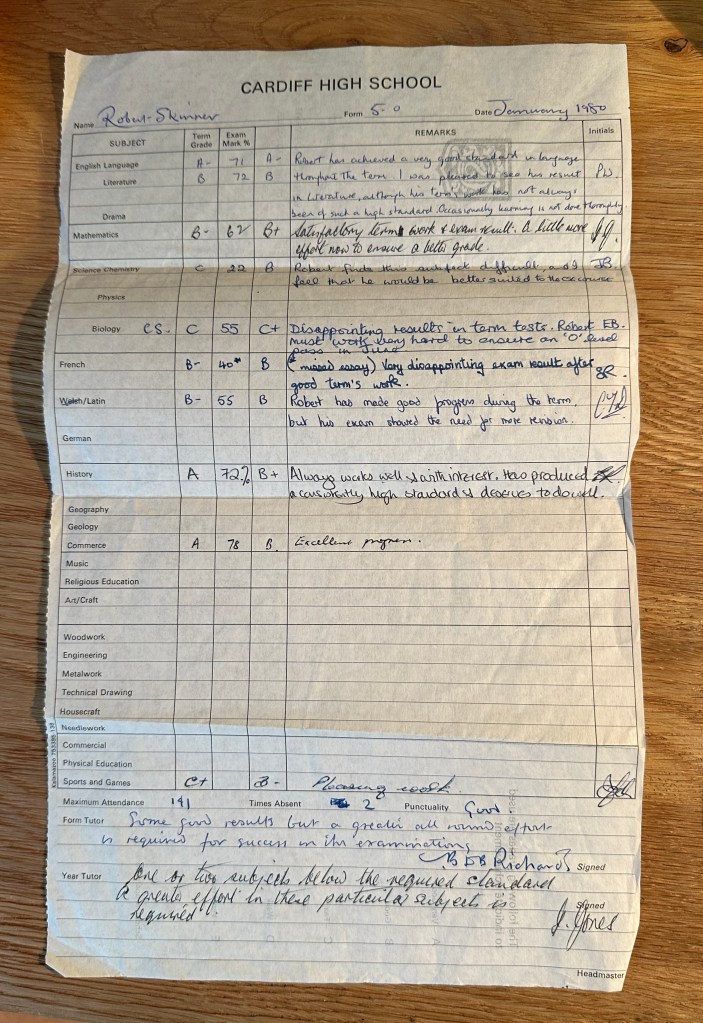

Callaghan was elected MP for Cardiff South in the Labour landslide of 1945. My late mother was covering one of his election rallies for the Penarth Times, and for years afterwards resented Callaghan’s disparaging public remarks about the paper when she questioned him.

He is the only prime minister to have held all the great offices of state: PM, chancellor of the exchequer, foreign secretary and home secretary. He observed that he didn’t find being PM harder than the other great offices. But he had the confidence in 1976 that came of his 30 years in politics, and 12 years of front bench experience. He was a good delegator, ‘preferring to sit back and let the others do the work’, and happily admitted he was never a workaholic. Today’s inexperienced premiers could learn from Callaghan’s example.

The Cardiff connection

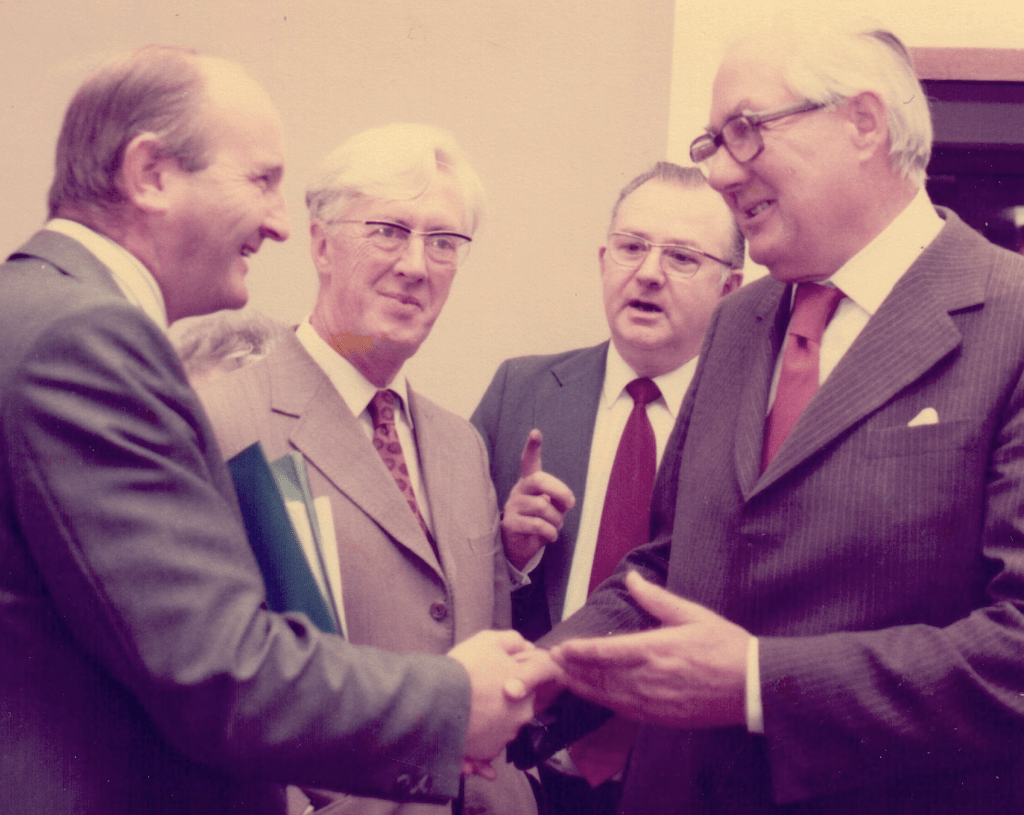

Amazingly, Callaghan was a Cardiff MP for 42 years, and continued as MP for eight years after his 1979 election defeat. That is unheard of today. He was a good constituency MP, as I discovered when, as a 22 year old graduate, I sought his help.

My father Bob Skinner was involved with the Cardiff Festival of Music. In 1985, Cardiff was due to host the world premiere of a work by a leading composer. On the eve of the concert, Dad discovered that two soloists from Hong Kong didn’t have the work permits needed to allow them to travel to Wales to perform. He thought that as the local MP and former PM Jim Callaghan could help. The two of us met Sunny Jim in his splendid House of Commons office (he was then ‘father’ of the House of Commons – the longest serving member), and he couriered a note to Conservative employment minister Alan Clark: “Come on Alan, as a Plymouth man make Drake’s drum beat again – for Cardiff!” The permits were issued within hours – the concert was saved, and proved a triumph.

What I didn’t know at the time was that Callaghan and Clark got on well, a not unusual example of cross-party friendships. In his famous diaries, Clark revealed that Callaghan asked to see Clark privately in his room in the Commons during the Falklands crisis in 1982. Callaghan was due to speak in the second emergency Commons debate about the Argentinian invasion of the islands, and wanted Clark’s advice on what to say. Clark said, ‘I have a rapport with Jim’.

Just before we said goodbye, Callaghan asked me as a new graduate what I wanted to do for a living. ‘I’d like to work in PR or journalism,’ I replied. ‘They all want to do that now, don’t they?’ Jim replied, more to Dad than to me. Within two years, I had started my 37 year career in PR.