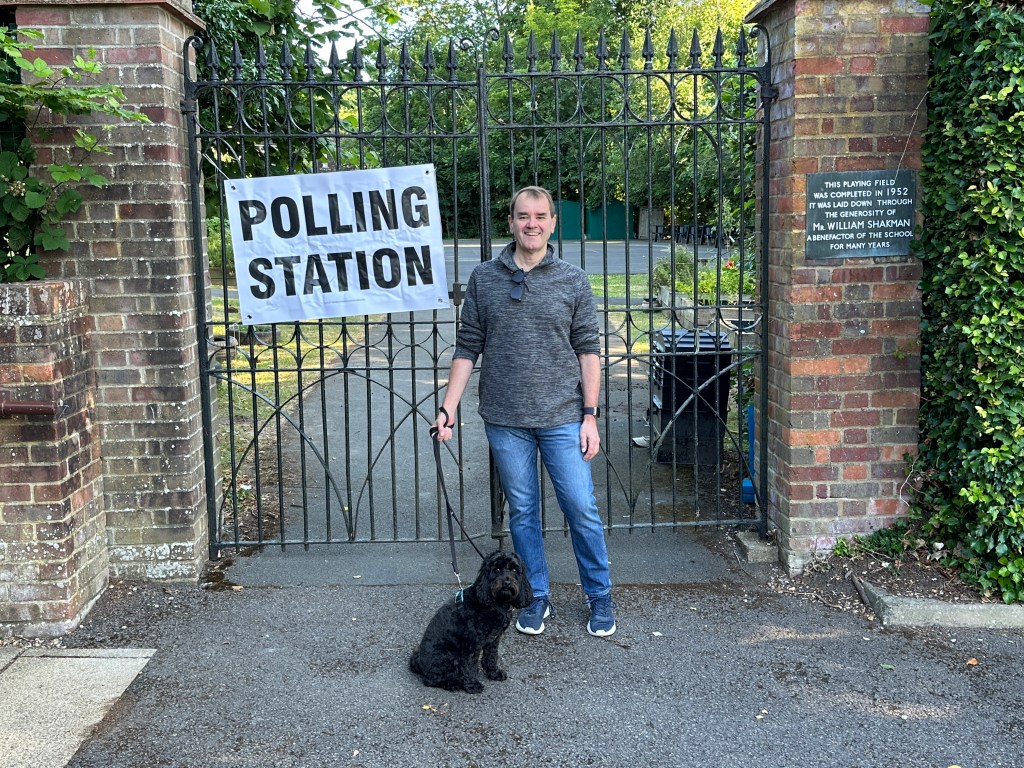

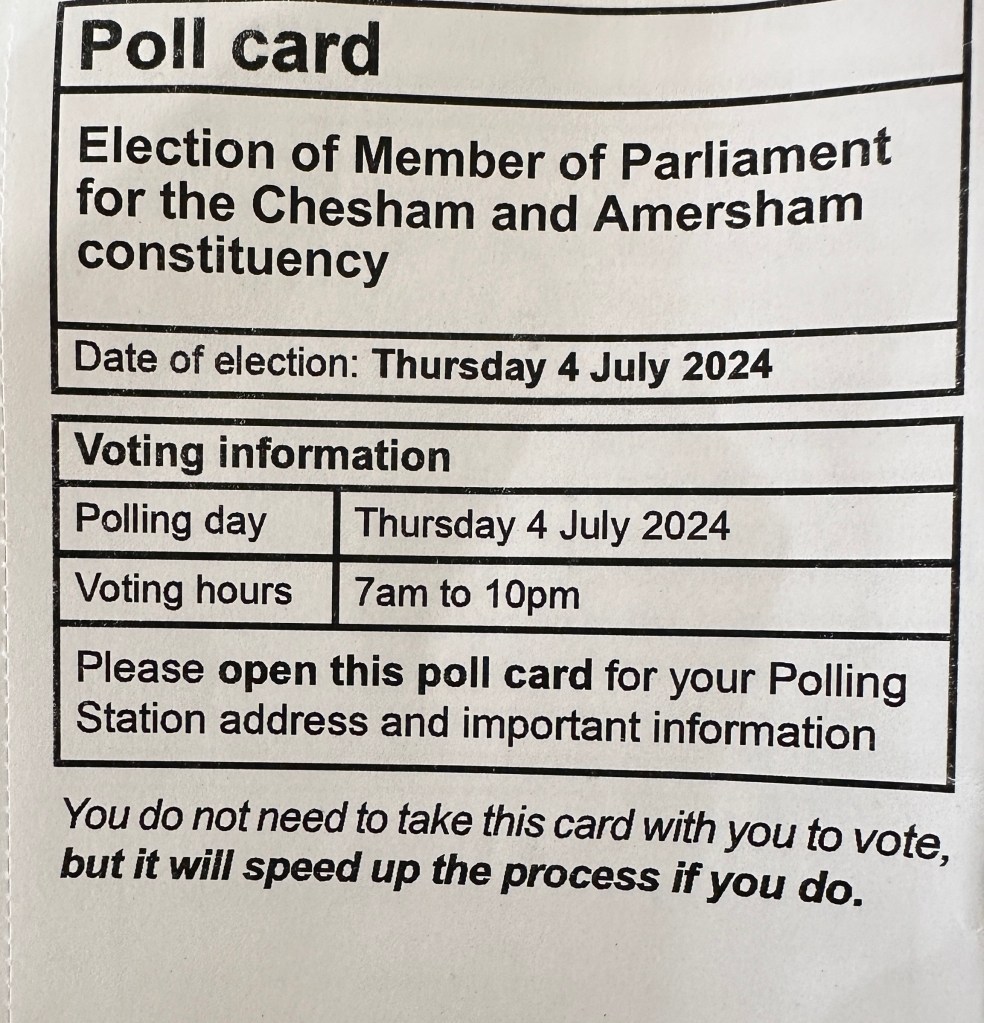

Vote early, vote often, as BBC Radio 4’s Weekly Ending satirical show said of the first Zimbabwean election in 1980. I followed that mantra today, voting in the historic 2024 general election before 8am. I then placed two further votes – but it was all legal, as they were proxy ones for two British friends who live in Switzerland. We took our lovely dog with us: #DogsatPollingStations.

I always feel humble when I go to vote. I’m conscious of the long fight for democracy in Britain and around the world. My grandmothers would have been in their thirties when they got the right to vote in the 1920s. (I don’t know if they satisfied the property qualification that was applied when women of 30 and above got the vote in 1918; if so, they’d both have voted in the 1923 general election that led to Britain’s first Labour government.)

Chesham & Amersham: the start of a democratic revolution

Living in Buckinghamshire, unless you are a Conservative you rarely vote for a winning candidate. Our constituency of Chesham & Amersham was a true blue seat, with Ian Gilmour representing the area for 18 years, followed by Cheryl Gillan until her death in 2021. Sarah Green sensationally took the seat for the Liberal Democrats in the resulting by-election. It was the first sign that the ‘blue wall’ of traditional Tory seats in Southern England was under threat as a result of disgust at Brexit and at Boris Johnson’s behaviour. (This was six months before partygate revealed how Johnson’s Number 10 spent the pandemic breaking its own Covid rules.) Green was born in Wales, like her predecessor, and made part of her maiden speech in the Commons in Welsh.

Brexit: the disaster that didn’t feature

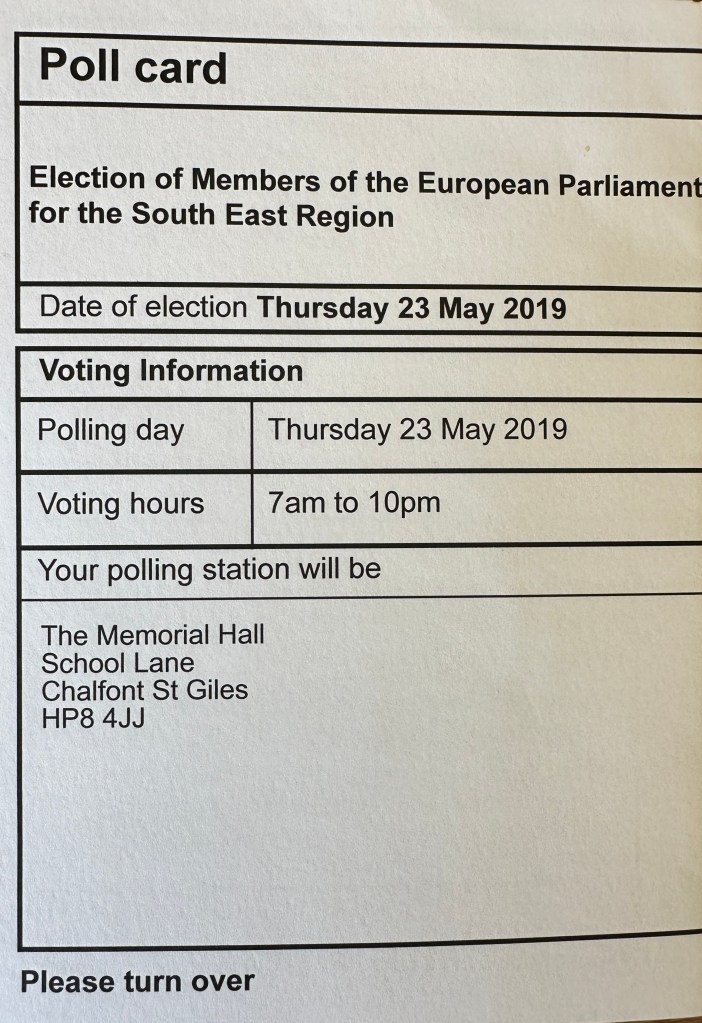

It’s poignant to reflect on this polling card, for the last European Parliament election that the UK took part in. We no longer have a voice in Europe because of the catastrophe of Brexit. It has posed painful extra costs and burdens on British businesses and people. Yet the Conservative, Labour and Lib Dem parties indulged in a conspiracy of silence about it during the campaign. (Credit to Plaid Cymru and the SNP for calliing out this conspiracy.)

Keir Starmer: Labour’s most consequential PM since Attlee?

Almost two years ago, I blogged that Keir Starmer was the quiet man would might transform British politics. If the polls are even remotely right, he is on track to secure Labour’s greatest ever election victory. It is an extraordinary achievement for a relatively inexperienced leader to replace a landslide defeat less than five years ago with a far bigger victory. (Though we should recognise that the Tories made the job far easier through lawbreaking and crashing the economy.) The Guardian’s Rafael Behr put it well in an election day column:

Nothing was inevitable. To make a Labour government look certain, to make so many people comfortable with the journey to Starmer’s Britain, to make it the obvious, natural destination at the end of the long-haul campaign is an achievement of rare political craft, not luck.

In that 2022 blogpost on Starmer, I longed for him to take Britain back into the EU single market and customs union as a bold first step, echoing Blair and Brown’s move to make the Bank of England independent of the government. But Starmer has thrown away that golden opportunity. It’s hard to see how the new Labour government can seriously grow the economy without it.

A different Britain

If Labour does achieve a historic victory, it will come into office at a time when the people can hardly believe that things will get better quickly. The country’s public services are on their knees. Our village is just one of many that have endured raw sewage in its rivers, streets and fields. Sleazy Tory politicians have waged culture wars on the attitudes of the young, while depriving them of the homes their parents and grandparents could afford. And our governing party has treated the law as applying to others, not themselves. Small wonder that people are voting tactically in the hope of seeing #ToryWipeOut2024. (My bet is the Conservatives will get around 110 seats, but would love to see them punished more severely for the damage they have done to the country.)

Keir Starmer and his government will have a grim inheritance. But what a change it will be to have a government that treats running the country seriously, rather than a game to impress the frankly unhinged columnists of the Telegraph and Mail. I hope a side effect of a big progressive win is that those toxic papers, along with GB News, will find themselves talking to themselves. It may even encourage the BBC not to amplify their unrepresentative rants.

It was 50 years ago…

Half a century ago, Britain saw two general elections in a year. The February 1974 election was the first I remember, as a 10 year old, when Harold Wilson returned unexpectedly as PM. Eight months later he went to the country hoping to secure a decent majority, but ended up with a mere three seat buffer. My main memory of that 10 October poll was breaking the cord of the light in our Cardiff loft! I wonder how today’s poll will be remembered in 50 years’ time by Britain’s school children – if at all.