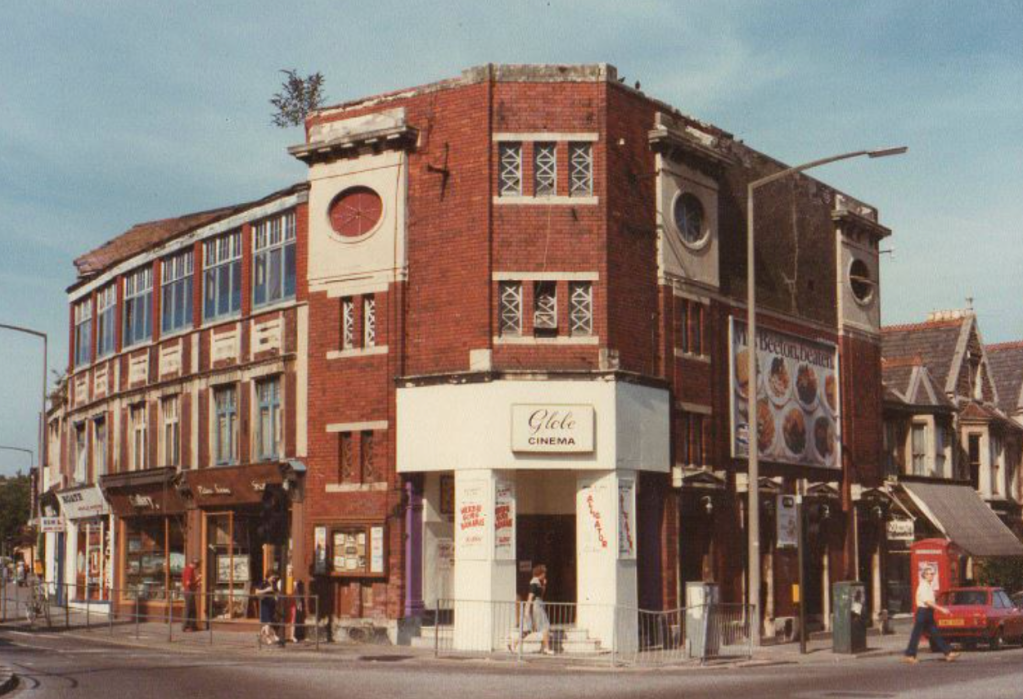

Above: the cinema in Empire of Light

Sam Mendes’ Empire of Light was not the film I was expecting. I was looking forward to a moving story about a neglected seaside cinema lovingly brought back to life. (Think Cinema Paradiso, Margate-style.) Instead, it was a far starker and more complicated tale of early Eighties Britain, with racism, mental illness and misogyny centre-stage.

I’ll share my thoughts on Empire of Light later. But this post is an unashamed exercise in nostalgia. The film revived long-dormant memories of childhood trips to the cinema in 1970s Cardiff. Going to the pictures (as parents, aunts and uncles described a trip to the cinema) was a very different experience 50 years ago, and Empire of Light brilliantly captures the mood of the time.

The first film I remember seeing in a cinema was Chitty Chitty Bang Bang on its release in 1968 when I was five. We also saw Earthquake, a 1974 disaster movie, in Elephant & Castle when we were staying in London for a weekend. (It featured sound effects designed to simulate an earthquake.) But most of my childhood big screen outings were in my hometown, Cardiff, Wales.

One Christmas, my father Bob Skinner took me to the old Globe cinema in Roath to see A Christmas Carol, which I now realise would have been the version that came out when Dad was 12 in 1938. (Dad’s favourite film.) The photos above capture the venue exactly as I remember it, with a bush growing out of the roof, and a shabby auditorium. (The moniker ‘flea-pit’ could have been inspired by the 1970s Globe.) In those days, films were often played on a loop, which gave rise to the expression ‘this is where I came in’. Sure enough, we stayed long enough to see the film starting again! Dad tells me that the cinema was run by a Welsh rugby international, whose wife worked in the box office. It was one of the first venues to show foreign films. The Globe closed in the 1980s, not long after my friend Anthony and I watched Return of the Jedi there – the only early Star Wars film I watched in a cinema.

Continue reading