So that was 2020. A year like no other in the past century. We now know the havoc a pandemic can cause – much as my grandparents did a century ago with the so-called Spanish flu. (Sadly, my grandfather’s twin brother died in that pandemic, having survived the Great War trenches.)

Our lives have been utterly changed. We can’t meet our friends. We have to wear a mask when buying a loaf of bread. Christmas may not have been cancelled, but it wasn’t the sociable highlight of the year we’ve known all our lives.

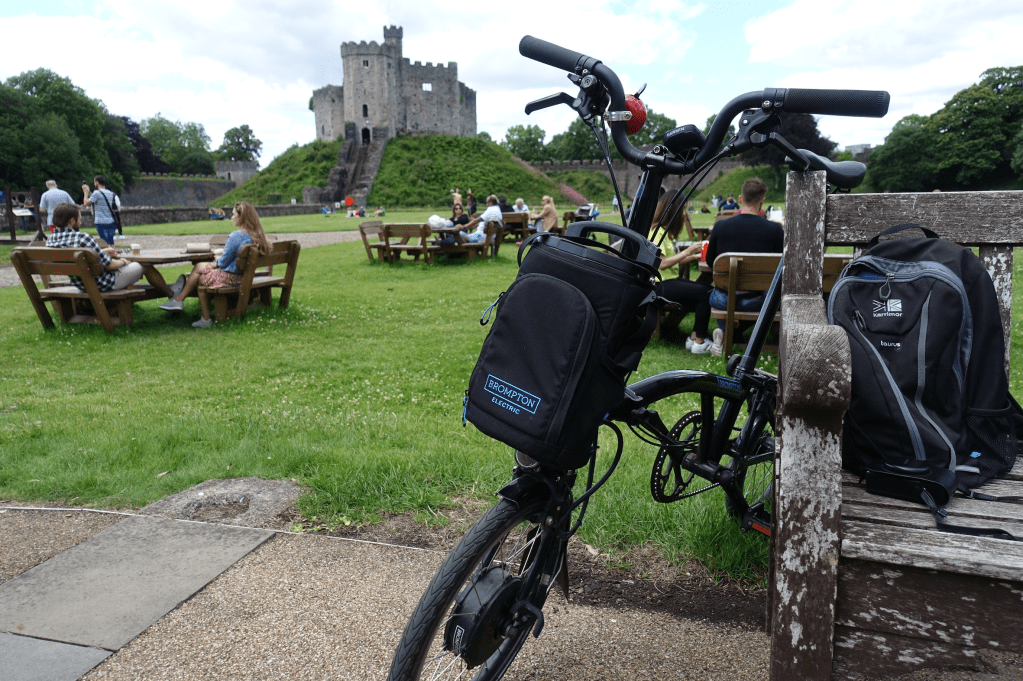

My lifeline, apart from family and the ability to work from home, has been my bike. Or trike. Getting into the saddle has been a joy in this joyless year. In those early lockdown weeks, in the most wondrous spring in living memory, I celebrated the empty roads and vibrant nature – whether the April blossom or the magnificent red kites overhead. I blogged about those magical spring days here.

Today, New Year’s Eve, I passed 3,000 cycling miles in 2020. It was a modest ride of under eight miles, with the temperature barely about freezing. I experienced cycling feast and famine this year, with a very slow start followed by four successive months of over 500 miles in the saddle. But as summer became autumn, I lost my enthusiasm for pedalling the same old local routes. I recorded just 65 miles in October. Yet that milestone of 3,000 miles was a powerful motivator as Christmas approached, and I recorded my highest ever December mileage of 313 miles – with many of these indoors on my Wattbike Atom with TrainerRoad.

In years gone by, I often blogged on New Year’s Eve about my cycling memories of the old year, and my cycling adventures planned for the year ahead. (This example from 2013 is typical.) Tonight’s post may not be as noteworthy. But I do have dreams for 2021. Only time will tell whether those dreams will come true.

Another coast to coast?

Back in 2017, I cycled across England from the Irish Sea at Whitehaven to the North Sea at Tynemouth on the famous Coast to Coast (C2C) route. It was a wonderful experience, despite unseasonal cold weather on the first day, and the struggle of the climb to Hartside on a bike without a low enough gear. As I contemplated possible challenges for 2021, a similar coast to coast adventure seemed perfect. Better still, Peak Tours, which proved magnificent as my Land’s End to John O’Groats tour company in 2019, offered just such a trip in May 2021 along the Way of the Roses, slightly further south, from Morecambe to Bridlington via York.

Will it happen? Will Britain – and especially England – have found, belatedly, a way of controlling the pandemic and rolling out vaccinations, allowing tourism to resume? We will find out. In the meantime, I will get training. I’ve found a combination of TrainerRoad sweet spot workouts on my indoor Wattbike and rides outside on wintry roads is a good way of gaining fitness out of season.

Meanwhile, I will reflect on previous adventures, especially in the region that I will be crossing (with luck) in May. Back in 2019, we cycled through Lancaster on LEJOG, seeing the effects of days of heavy rain, as seen above. I also remember with affection cycling through the northern fell country on my earlier LEJOG in 2002. Perhaps I will get the chance to stay in my favourite hotel of the 2019 LEJOG, The Mill at Conder Green.

Here’s to 2021’s adventures.