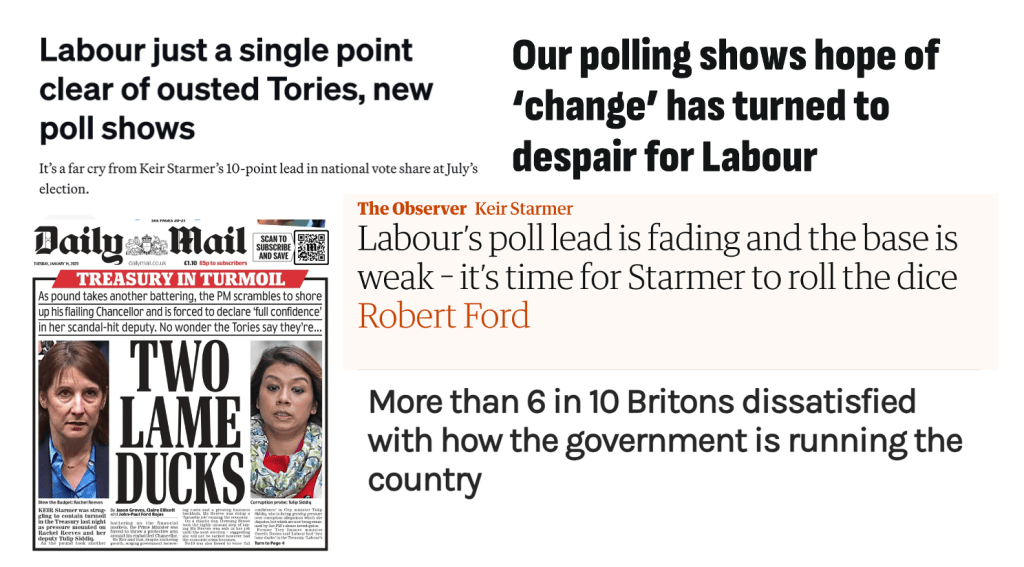

This is a bleak midwinter for Keir Starmer’s Labour government. Elected by a landslide just six months ago, Labour is sinking fast in the polls, and the modest enthusiasm that greeted its election has long since disappeared. Strategic messaging and policy mistakes have led to despair amongst many supporters, and jubilation from the populist insurgent party, Reform UK, now neck and neck with Labour in the polls.

True, at least some of the backlash is the traditional reaction to a Labour government from Britain’s dominant right wing press. All too often the BBC falls for the mistaken view that it has to amplify every right wing criticism of Labour. And people tend to be more fickle these days – a trend that benefitted Labour as it went from its worst election defeat for 84 years in 2019 to a landslide victory last year. But most observers accept that Labour has made an exceptionally poor start, even allowing for its dreadful inheritance.

Lessons from Thatcher’s experience

Labour’s collapse in support and morale so soon after being elected is very unusual, especially for a party winning power from opposition. The only comparable example, ironically, is an encouraging precedent for Labour. Margaret Thatcher has now passed into legend as the iron lady: indomitable, unyielding and triumphant, at least until hubris took over after her third election win in 1987. The reality is more interesting.

In the autumn of 1981, Margaret Thatcher was under siege. Just over two years into her premiership, her monetarist economic policy (trying to reduce inflation by controlling the amount of money in the economy) had proved disastrous. Having condemned Labour for presiding over rising unemployment (‘Labour isn’t working’ in the words of an infamous poster) and inflation, the Thatcher government’s policies contributed to far more job losses. In her first three years, Britain lost a quarter of its manufacturing capacity. The nightly news bulletins were dominated by reports of yet more famous brands laying off staff, or going bankrupt.

The cause in many cases was the soaring value of the pound, caused by high interest rates, which made our exports hugely expensive. (In late 1979, chancellor of the exchequer Geoffrey Howe raised interest rates to a crippling 17 percent largely because investors were not willing to lend money to the government – the so-called gilt strike, which shows that the gilts (government bonds) crisis that did for Liz Truss had an unexpected precedent in her heroine’s traumatic early years.)

Continue reading