This post recounts the first day of my English Channel to the Mediterranean cycle tour in France with Peak Tours in June 2025.

Prologue: Sword beach, Ouistreham

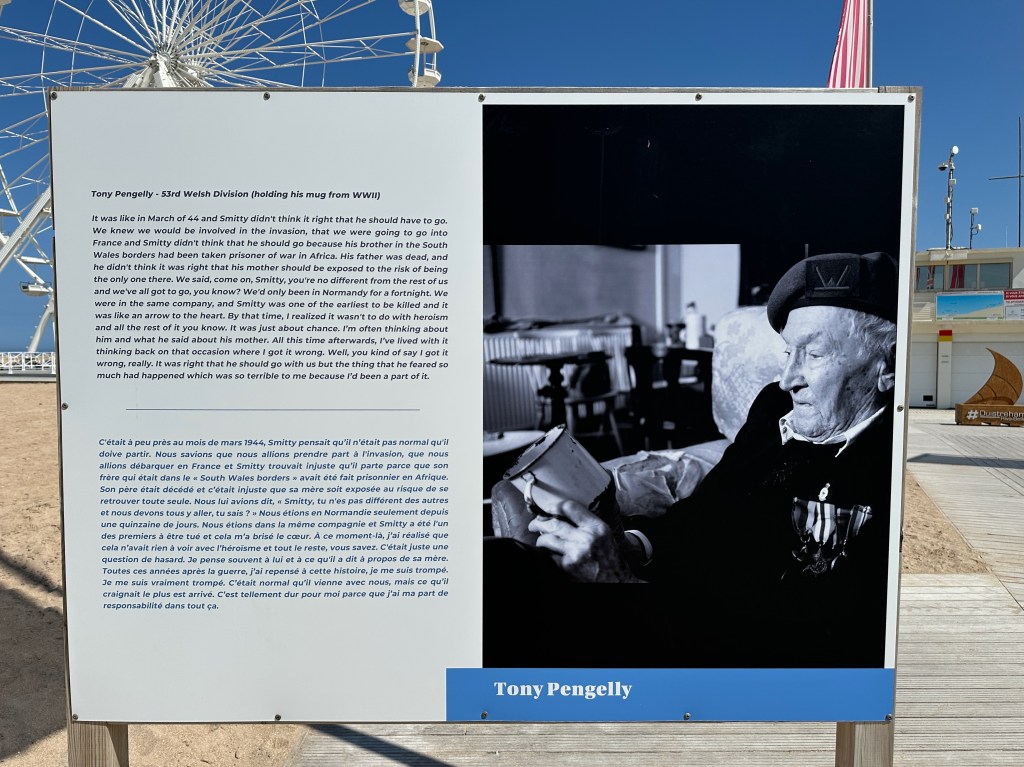

Today. Ouistreham is a peaceful place to land in France. But as I walked along the sand with the English Channel by my side, I marvelled at the stark contrast with the experience of the men who fought their way up this beach – immortalised as Sword beach – on 6 June 1944. I reflected on the individual stories told on a series of plaques along the beach walkway, such as fellow Welshman Tony Pengelly, featured in a photo above. These men were just a year or so older than my late father Bob, who joined the British Army himself some six months after D-Day on turning 18. However tough I found cycling from here to the Mediterranean, it would be nothing compared with the hell endured by that extraordinary generation of men and women of many nations as they liberated Europe over 80 years ago.

An easy start

Our long journey to the Mediterranean began at the fish market at Ouistreham, following the west bank of Caen canal to that city. As we set off I realised my Garmin was still set to kilometres following last weekend’s Bryan Chapman Memorial 600km audax ride in Wales. I switched back to miles, just to make it easier to cross reference the Peak Tours route directions in case of Garmin issues. This proved a smart move…

Just three miles into the ride, we came to Pegasus Bridge at Bénouville. British troops captured this critical crossing just 26 minutes into D-Day, a mere 90 minutes after taking off from Dorset in Horsa gliders, and hours before the landings on the Normandy beaches. The bridge that we saw was a 1990s replacement of similar design to the 1934 original, which is now in a nearby museum.

We didn’t have time for a coffee at Café Gondrée, whose wartime owners were active in the French resistance. I was once served by their daughter Arlette, who took over this historic institution after her parents died. She is now in her eighties. One of our party recalled meeting the legendary older Gondrée owners in the 1970s.

Our first navigational doubts came in Caen, but we reached a consensus and continued on the right route. Today’s city lacks the character of many historic cities across Normandy because of its near total destruction in the weeks after D-Day. The Allies hoped to capture Caen on that critical day, but its liberation came six brutal weeks later, at a bitter price: the loss of 30,000 Allied troops, 3,000 civilians as well as the loss of most of the historic city.

After we left the canal, we followed an old railway line south of Caen. This is now part of the Vélo Francette, a marked cycle route that wends its way to La Rochelle on the Atlantic. It reminded me of the Tâmega trail on my Portugal end to end tour in 2023. Some 18 miles after setting off, we had our first ‘brew stop’ near Amayé-sur-Orne. These morning and afternoon stops are a brilliant idea by Peak Tours, as I found on my first tour with them in 2019, Land’s End to John O’Groats. They guarantee you will be well fuelled for the remaining miles to lunch or your afternoon destination. (The Yorkshire Tea was popular – even in the heat of later days!)

It was fun weaving our way through the families enjoying their Saturday morning activities at Thury-Harcourt. It was here that I nearly came a cropper after misjudging my path between barriers across the trail. But all was well.

We were now following signs for Suisse Normande (Swiss Normandy). While Normandy is hardly mountainous, the name does confirm that it has its fair share of hills, which we’d be climbing after lunch at Clécy. We were briefly delayed by two moments of navigational uncertainty on either side of the bridge over the Orne. Once again, the route notes solved the riddle: ‘cross over the [river] bridge’ and turn left after ‘some recycling bins’ proved conclusive. It is curious how cycling satnav devices occasionally prompt such doubts compared with car navigational systems. You’d think our slower speeds would prove ample time to display the exact turns – or is it the fault of the GPX route files that we use?

I’d been looking forward to seeing Clécy after staying here on two cycle tours in 1998. I stayed in the loft of an outhouse in the garden of a hotel on both occasions – which featured in a photo in a Normandy guide! We had a steep climb up to town from there. Only after we passed through this time after an enjoyable lunch at the Aux Rochers restaurant did I realise that my 1998 stop was on the other side of town, away from the river.

Now the climbing began. Unlike later in the tour, these were short if sharp ascents, but they came in quick succession. It was a pleasure to pause to take photos in Pont d’Ouilly, with its eponymous, handsome bridge over the Orne. Soon after, I overtook a few touring cyclists, and smiled when I saw a baguette poking out of one of their panniers. Over the coming weeks, we’d see many laden touring cyclists. I was once one of their number – see my account of a tour of Brittany in 1996 – but am glad to leave others to carry my luggage today.

As the miles passed after lunch, with one climb after another, I was dismayed to see my Garmin telling me that I’d only completed 700 of the 3,000 feet of climbing for the day. But then I looked closer, and realised that it was showing 700 metres of ascent. Changing the device’s measurement from kilometres to miles this morning obviously hadn’t switched ascent to feet. That meant far fewer hills remained to be conquered.

This called for a celebration. We stopped for a pastry at this wonderful pâtisserie in the village of Les Monts d’Andaine. It was an indulgence as we barely had five miles still to ride, but it was worth it. It was wonderful to find such a classy pâtisserie in a small French town.

Our destination, Bagnoles de l’Orne, was just as I remembered it from staying here in 1998: a rather elegant, small spa town with a small lake at its heart. The tranquility was slightly disturbed by some kind of festival taking place on the other side of the lake from our modern hotel.

This evening, we had our welcome dinner. Peak Tours usually holds these on the eve of the first day’s cycling, but as some prefer to join the Channel to the Med trip by overnight ferry the morning of departure they wait until the first evening on the road on this tour. So we’d already started to get to know each other by the time we sat down for drinks and dinner at Bagnoles. There was, however, a shadow over proceedings: we learned that one of our riders had been taken to hospital after an accident just after lunch. As a result, the guides were very busy supporting him. Sadly, he never rejoined the tour, but happily recovered from the crash.

Read Day 2: Bagnoles de l’Orne to La Flèche

The day’s stats

67.93 miles, 3,205 feet climbing, 5 hrs 12 mins cycling, average speed 13.1 mph.