Labour won a landslide victory in July’s general election, as the Conservative Party was swept from power after five years of law-breaking, financial incontinence and plain incompetence.

Keir Starmer’s narrative since taking office two months ago has been clear and consistent. Things are even worse than Labour feared, and the Tories are to blame.

This is a straight copy of David Cameron and George Osborne’s 2010 playbook, which pinned the blame for the 2008 financial crisis on Gordon Brown’s Labour Party. Labour was never able to shift the narrative to highlight the bold action Brown took to counter the crisis.

There are also echoes of Margaret Thatcher’s success in reminding voters of the chaos of the 1978/79 winter of discontent under Labour at every opportunity throughout the 1980s. For years, Tory party political broadcasts would show film of mountains of rubbish in the streets and picket line violence accompanied by a funereal voiceover intoning, “In 1979…” in case anyone had forgotten life under Labour.

But pinning the blame on the Tories won’t be enough for Starmer. The electorate gave a firm verdict on the Tories at the election: guilty. Labour must do more than simply emphasise what the voters have already decided. Starmer needs to become a political teacher, in commentator Steve Richards’ perceptive phrase.

Richards noted that the most successful modern British prime ministers – Thatcher, Blair and to some extent Wilson – did more than assert a political viewpoint. They realised they had to explain their vision and actions. Thatcher, for example, famously used the analogy of the household budget to explain that Britain could not spend beyond its means. (Critics disputed the parallel, but to little effect.) Blair was an even more effective communicator, combining clarity with the verve of a religious preacher. Under the New Labour, New Britain banner, he explained why the party and the country had to change. Although New Labour was accused of spin, Blair gave long media interviews and press conferences, engaging with the big issues of the day with seriousness and skill.

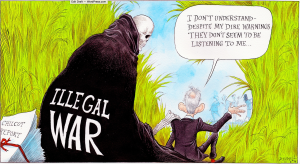

Starmer and team were understandably paranoid about losing the election. But they must now move beyond the doom-laden narrative of the government’s first two months to set a positive, optimistic vision for the next five years. This has to be done quickly. Starmer must avoid becoming another Theresa May: her utter inability to communicate let alone explain to the nation and her party what she was trying to achieve doomed her premiership especially after the catastrophic result (for her) of the 2017 general election. As Steve Richards put it, ‘She not only failed to tell her story, but did not even make an attempt. This was her fatal flaw – not only a failure to communicate, but an indifference to the art’. (The Prime Ministers: reflections on leadership from Wilson to Johnson, 2019)

Another judgement from Steve Richards about Theresa May strikes me as a stark warning to Keir Starmer: ‘She did at times have space on the political stage, but failed to see when she had the room to be bold and when she did not…. she acted weakly when she was politically strong…’ I fear Starmer may fall into the same fatal trap.

Even Blair’s own record in government provides a warning. On 2 May 1997, he was in complete control of the political landscape (even if he shared that control with Gordon Brown). Yet his first term was a story of paralysing caution aside from devolution to Wales and Scotland, the national minimum wage, and the historic Good Friday peace agreement in Northern Ireland. (His Tory predecessor, John Major, deserves credit for building the foundations for peace, but Blair’s masterful political artistry proved critical.) Soon after New Labour’s second landslide in 2001, the 11 September terrorist atrocities followed by the Iraq war stole what momentum Blair’s government might have achieved. I sense that if Starmer doesn’t seize the opportunity to become a political teacher now, voters will lose faith far more quickly than they did with Blair, especially as Tony enjoyed a golden economic inheritance from John Major.

Much will depend on chancellor Rachel Reeves’ budget on 30 October. Labour has already spun this as a budget of hard choices – forced on us thanks to the Tory financial black hole. And Reeves has already cancelled a host of rail and road projects, and the Edinburgh super computer intended to give Britain an advantage in the artificial intelligence race. It remains to be seen whether Labour will win the political intelligence race.

Cameron and Osborne won the argument in 2010 about Labour’s responsibility for the financial crash. But their remedy, years of austerity, has caused enormous damage to the fabric of the nation, especially public services. Funding for local government in England has been slashed by 55 percent in real terms since they took office in 2010. (Source: IFS.) All this was a factor in voter contempt for the Conservatives in July. After the Liz Truss catastrophe, Labour has to be prudent with public finances, but I fear that Labour is falling for the coalition’s slash and burn approach, much as it has stolen Cameron and Osborne’s blame playbook.

Lessons from history

Labour’s landslide win in July was bigger than the party’s famous win in 1945. (Although on a far smaller share of the vote.) Labour’s 1945 leader, Attlee, was even less charismatic than Starmer, but his government changed the country with the birth of the NHS and the welfare state, and independence for India. Yet it was out of power within six years. By 1951, voters were no longer prepared to put up with austerity and ‘jam tomorrow’ – food was still rationed years after the end of the war.

Starmer is a fan of Harold Wilson, who lost the 1970 election just four years after a landslide victory. Voters today are even less patient than 50 years ago, and Labour needs to heed these lessons from history. Lead the nation with a compelling story and show serious improvements to Britain’s shameful public services by 2028 and Labour has the chance to be the natural party of government for the 2030s.

Postscript: Jenni Russell makes almost exactly the same argument in her column in The Times three days after I published this blogpost. (Paywall.)