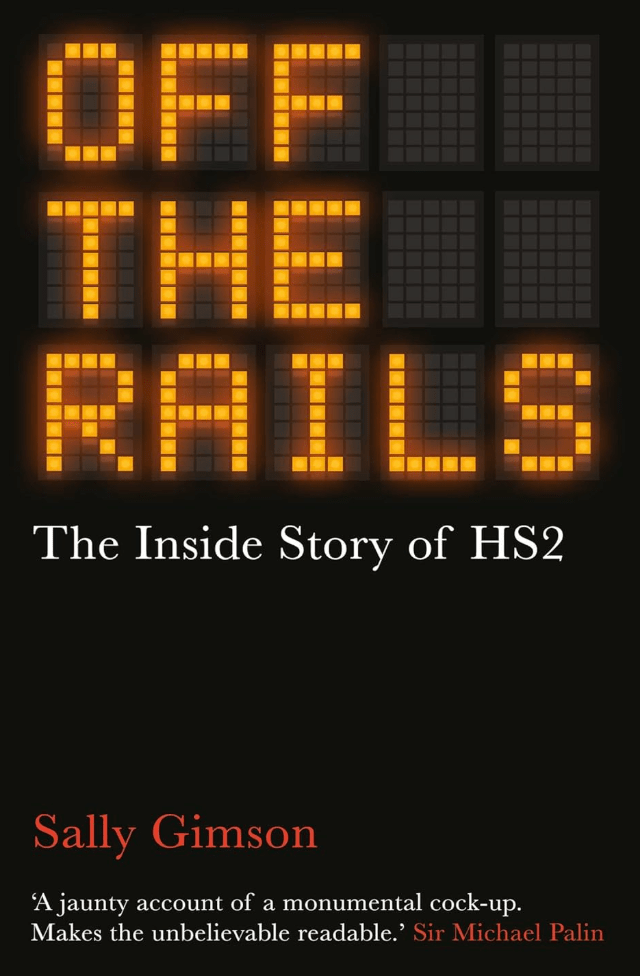

A review of Off the Rails, The Inside Story of HS2 by Sally Gimson. (Oneworld, 2025)

If any project deserves a detailed exposé, it’s HS2. Britain’s plan to build a second high speed rail line has become an epic, expensive failure. Once heralded as giving the country – well, England – a network of high speed routes between London, Manchester, Nottingham and Leeds, it has been reduced to a single route between London and Birmingham. Thanks to the stupidity of former prime minister Rishi Sunak, who cancelled the Birmingham to Manchester section, HS2 trains heading for Manchester could actually be slower than today’s trains once they divert from HS2 onto the West Coast Main Line at Handsacre Junction north of Birmingham.

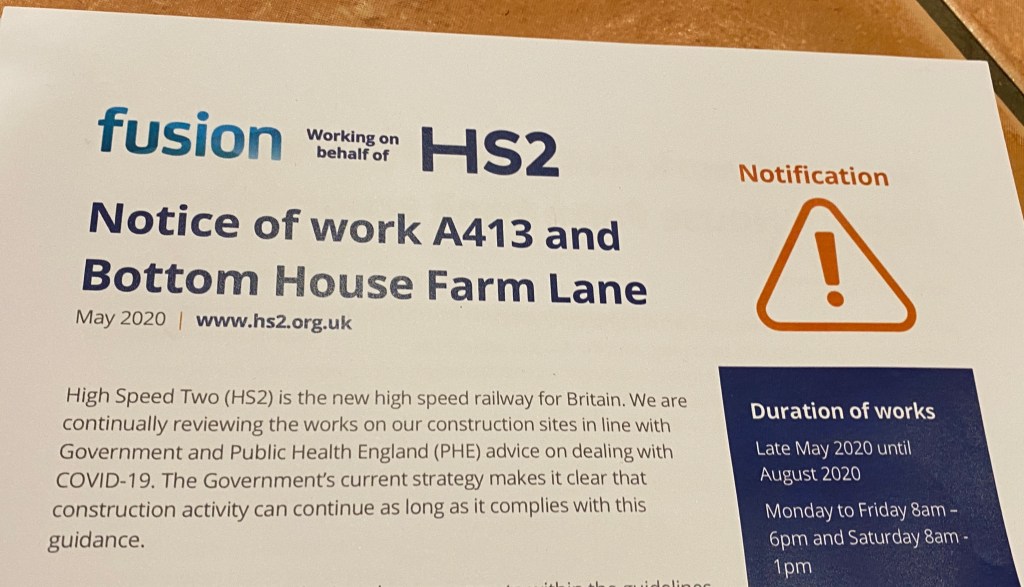

Our village, Chalfont St Giles in Buckinghamshire, is on the route of HS2. You’ll find few supporters of the project in these parts, even though the line passes us in the 10 mile long Chiltern tunnel. But I always supported the idea, as I blogged when the Tory-Lib Dem coalition gave the green light to HS2 in 2012. As I argued:

‘Britain’s intercity rail network was born just before Queen Victoria came to the throne in 1837. It was the wonder of the world. Nearly two centuries later, the world wonders why Britain is so reluctant to build a new railway. HS2 opponents say we should just modernise the west coast mainline. That line was created from a series of 19th century railways. It has been ‘modernised’ twice in the last fifty years. It’s still in essence a Victorian railway.’

Above: HS2 built a new road parallel to Bottom House Farm Lane, Chalfont St Giles, for construction traffic to the site of an HS2 tunnel shaft

Our former MP, the late Cheryl Gillan, features heavily in Sally Gimson’s story. If you’re wondering why HS2 is proving vastly expensive compared with similar lines in France and Spain, Gillan is one one of the many reasons. Protesters in the Chilterns were bought off with miles of extra tunnels. These same protesters will happily use Heathrow airport, the M40 and other environment-shredding services. (As I do, I hasten to add.) Ironically, the route from Birmingham to Manchester, killed by Sunak in 2023, would have been far cheaper to build with fewer tunnels and viaducts.

HS2’s advocates and planners didn’t help by changing the reasons for the line. It started out as a need for speed – though arguably faster than we needed, increasing costs – but morphed into a boost of the capacity of the railway, followed by an idea of ‘levelling up’ the country.

Sally Gimson tells the story well, from early mistakes through soaring costs resulting from buying off Chiltern protesters right up to Rishi Sunak’s calculated act in announcing the axe of the route to Manchester … in Manchester. She’s a fan of the concept of HS2, and is appalled by the way the project’s epic mismanagement has given high speed rail in Britain a terrible reputation, despite the success of HS1.

She doesn’t explain that the British government designated HS2 an ‘England and Wales’ project, even though even the original route didn’t include a metre of track in Wales. This meant that Wales was denied extra funding for rail projects under the Barnett formula unlike Scotland and Northern Ireland, which gained billions of pounds of extra funding. This has been hugely controversial in Wales, especially to the Labour government in Cardiff after Keir Starmer refused to reconsider the decision on coming to power.

Sadly, Gimson’s book is riddled with silly factual mistakes that suggest a shaky grasp of railway history – and more. Here are some that I spotted:

The Times newspaper was not a product of the railway era (p23) – it was founded in 1785, decades before the start of the railway era.

HS1 did not open in 2001 (p43). The first section opened in 2003, with the second section to St Pancras following in 2007.

Crewe was not still building steam locomotives in 1964, the year Japan’s first high speed line opened (p47). Crewe ended steam engine construction in 1958, and the final BR steam locomotive, Evening Star, was completed at Swindon in 1960.

British Rail was not born a year after the railways were nationalised (p34). Nationalisation on 1 January 1948 created British Rail under the original longer name, British Railways.

Northern Rock bank collapsed in 2007 not 2008 (p66).

There was no ‘InterCity125 line connecting London to Edinburgh developed in the 1980s’ (p131). The InterCity 125 service from London to Edinburgh began in May 1978, using the existing East Coast Main Line. The line was electrified in late 1980 with InterCity225 electric trains reaching Edinburgh in 1991.

Andrew Gilligan resigned from the BBC in 2004 not 2003 (p169).

Graham Brady oversaw the vote of no confidence in Theresa May by Tory MPs in 2018 not 2019 (p189).

Andy Street was not elevated to the House of Lords in December 2024 – or at any other time. He is not Lord Street, but Sir Andy Street. (p213.) Also, he was not chair of John Lewis, but its managing director.

Neville Chamberlain was lord mayor of Birmingham in the 20th not 19th century (p222).

It was the Grand Junction not Grand Central railway that built Crewe (p243).

I’m sure Christian Wolmar, a real transport expert, would have spotted the transport howlers had Gimson asked him to proof read her manuscript.