It was like opening a time capsule. When my grandmother died aged 88 in 1981, we entered her house, 15 Grove Place, Penarth, Wales with trepidation. She had been a virtual recluse in her final years, and we found a house barely changed from my mother’s childhood there in the 1930s. The front room was kept in Sunday best condition, with an elegant settee, probably bought before the war from David Morgan, the Cardiff department store that had a branch in Penarth. On the wall of the main room was the 1969 calendar that I’d made for Grandma in my first term at school, aged five. (I had stuck a miniature 1969 calendar onto the bottom of a picture I’d drawn, no doubt guided by my infant school teacher.)

I made a beeline for the books kept in the middle room of this solidly built Edwardian (or late Victorian) house. There I found the two volumes of David Lloyd George’s Great War memoirs, still in the postage box they been came in on publication in the 1930s. But far more intriguing was a small Bible, with the year 1866 written in ink on the first page. As I opened it, a couple of very flimsy pages fell out.

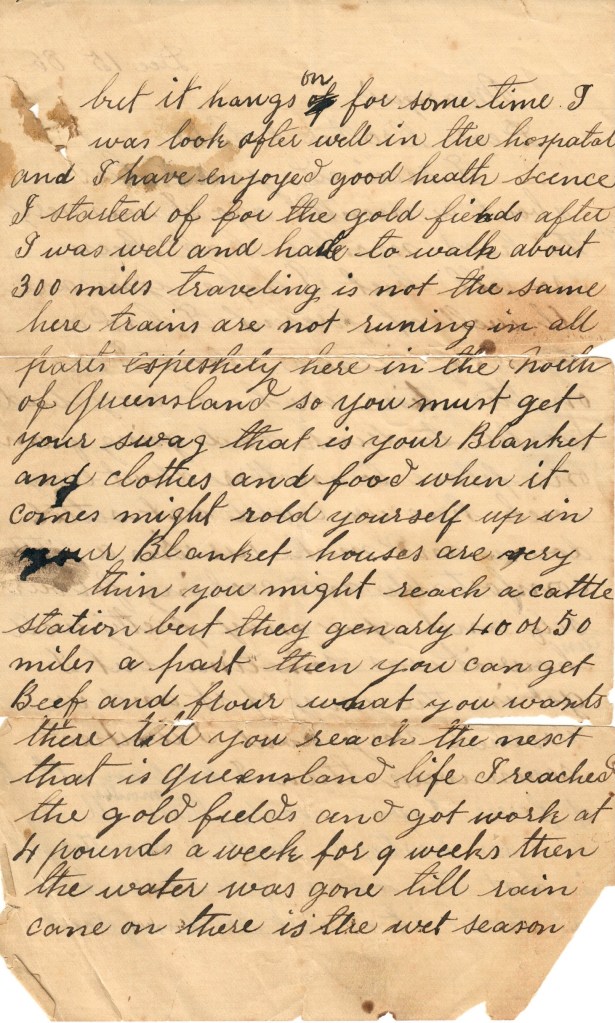

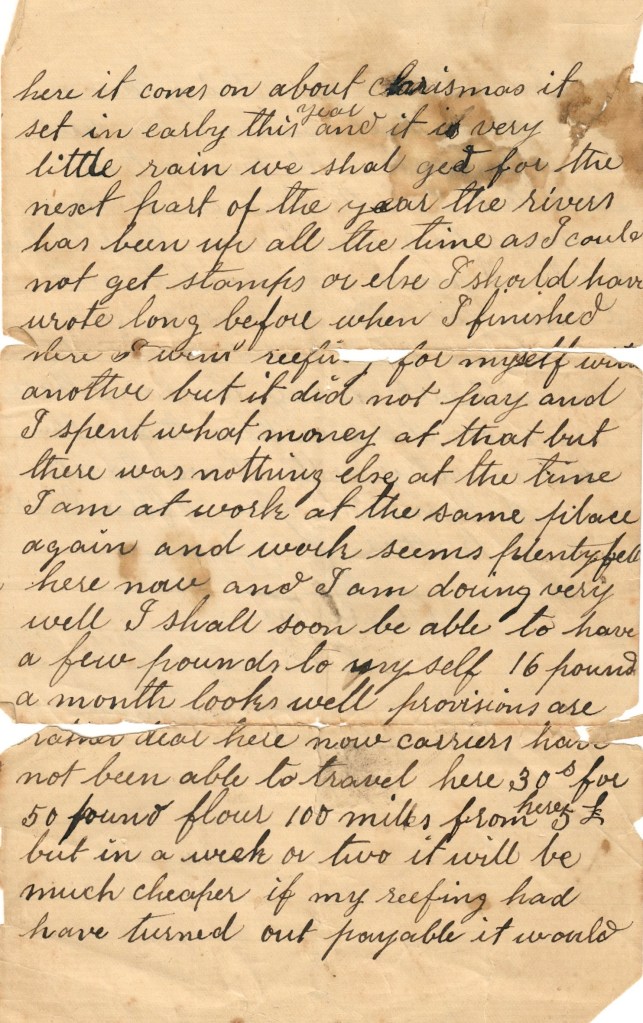

Above: the letter, written on both sides of two sheets of paper.

I was amazed to find that this was a letter written from the Australian goldfields in 1886, presumably by one of my ancestors. It was an incredibly poignant tale. The writer – who signed his name merely as C Preece – expressed his sorrow that his mother had been very ill, but explained that he’d been ill himself with a fever:

I had an attack of fever I was nearly three months ill I was in hospital about 2 months it is not the same fever here has at home it is not dangerous but it hangs on for some time…

It’s clear from the letter what a hard life awaited those who travelled to Queensland in the hope of making their fortune. The writer mentioned walking 300 miles because of the lack of railways in that part of Queensland, and also says how expensive provisions were, saying that 50 pounds of flour cost 30 shillings. (As a rough guide, that’s equivalent to around £220 in today’s money, which is a contrast with today’s price of around £20 for the same amount of flour.)

The writing in the letter is that of someone who’d received a very basic education – like many in mid 19th century Britain. As a result, his meaning is tantalisingly ambiguous. Talking of how much he was earning, he tells his brother and sister that ‘£16 a month looks very well’ – was that an aspiration, perhaps inspired by what he’d heard others had made, or what he’d actually earned? If he had, it would represent a fabulous month’s income of around £20,000 in today’s money. (These modern money conversions are based on Measuring Worth, a very helpful online calculator recommended by the Rest is History podcast.) Or is he deliberately talking up his prospects to reassure his anxious siblings back home? He does end by saying there are ‘more chances here than [in] the old country’.

Where was the ‘Charlston Etherage Goldfields’ in Queensland?

When I first read this remarkable letter in 1981, I was vaguely aware of the Australian gold rush, but had no idea where the Etheridge goldfield was. I wasn’t surprised to find no clues in my schoolboy atlas (The Times Concise Atlas of the World, 1975), and that appeared to be the end of the quest. Until the advent of the internet…

The breakthrough came when we were planning our 2026 family holiday to Australia. Queensland was on the itinerary, and I wondered whether we’d be able to visit the goldfields. As a result, I was able to confirm where that long-dead ancestor sought his fortune. The town of Charleston was renamed Forsayth after the arrival of the railway from Cairns in 1910. Forsayth is in the shire (county) of Etheridge, echoing the name of the goldfield. Unfortunately, it’s over 400km inland from Cairns, so it won’t be possible to include it in our itinerary. One day…

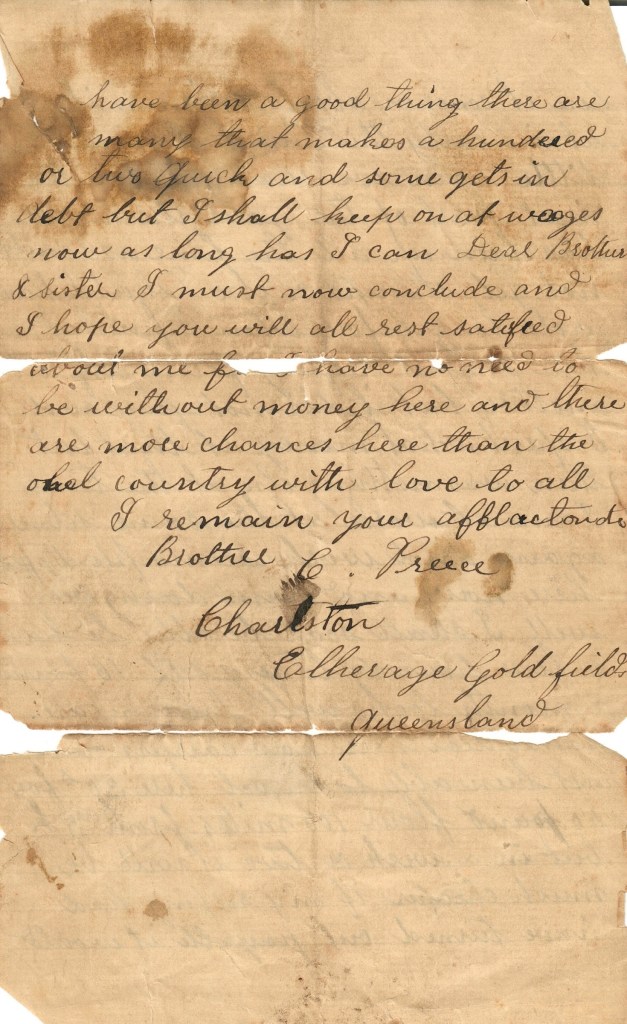

Clues from the family Bible

Almost 45 years after first discovering that small Bible, I decided to find out more about the people whose names appear inside. The front inscriptions were (presumably) by the person whose name appears there dated June 1866: Elizabeth Williams, Bredwardine, Herefordshire. At the back of the Bible is a sad note that says:

Elizabeth Preece/Departed this life/May 20th 1893/Aged 39 years/And 9 months

Underneath is written the same date, May 20 1893, presumably by Elizabeth’s grief-stricken husband, just hours after she died.

On the second page of the Bible is the above record of the births of Elizabeth Preece’s children, William Charles and Albert, my grandfather. I was keen to find out more, and that could only be done online as my mother’s family knowledge died with her in 2018.

Within a few minutes I’d downloaded from the General Register Office a digital copy of Elizabeth’s death certificate, above, which showed that she died of albuminuria, which is associated with kidney damage. The document showed that her husband, William Preece (senior), was with her when she died.

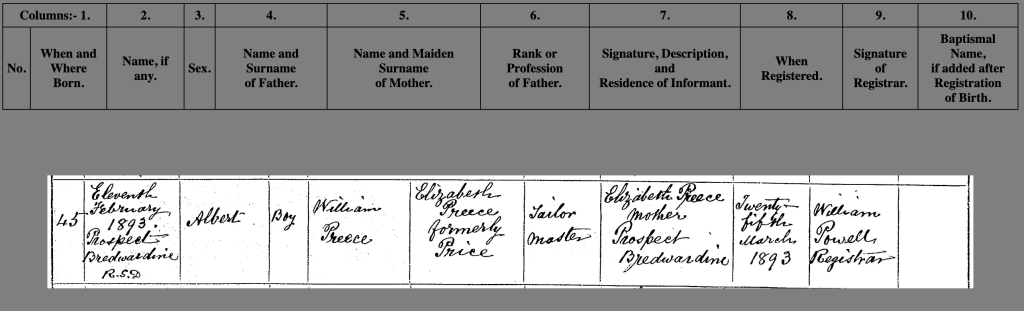

My next task was to find the birth certificate of my grandfather, Albert Preece – known to me as Grampy. This confirmed that his parents were Elizabeth and William, and, very poignantly, that Grampy was born three months before his mother died. I wonder if his mother’s illness was a result of a difficult pregnancy – far more dangerous 133 years ago than now? However, there was one mystery: Elizabeth’s maiden name was given as Price, not Williams. Was Elizabeth Williams another relative? Incidentally, the surnames Preece and Price are both anglicised versions of the traditional Welsh name ap Rhys (son of Rhys).

Just to complete the set, I obtained William junior’s birth certificate, seen above. He was born on 21 November 1891, when his parents were living at Cold (actually Cole) Brook Cottage, Bredwardine. They had moved to Prospect, Bredwardine, by the time his brother Albert was born two years later.

I knew my grandfather was born in the lovely border village of Bredwardine, but was sure I’d seen a reference to his living in Brecon. Was that on another book or document that was lost when my parents cleared out the house in Penarth after Grandma died? As no one alive today could offer any clues, the next step was to consult census records.

A search on the 1901 census drew a blank for Albert, his brother and father. But the 1911 census produced this intriguing entry. Albert was indeed living in Brecon, but with his aunt Margaret and uncle Thomas. Also living with them was another nephew of the householders, Reginald (?) Pugh. Was that another sibling of Albert – or a cousin? Amusingly, whoever filled in the form at first filled in the nationalities of the residents as English or Welsh, before crossing out these entries as nationality information was only required for those born overseas. Margaret is marked as speaking Welsh and English, while the others spoke only English – not surprising in this border county. Albert had already started a printing apprenticeship – he went on to become a newspaper linotype operator, retiring in the early 1960s.

I then did a search for Albert’s brother, William. According to the 1911 census he was also living with an aunt and uncle – Thomas and Eliza (?) Worthing, in Hay on Wye. He was then aged 19, and working as a carpenter and joiner. The great unknown is what happened to Albert and William’s father. Had he died? There seems no other reason why both his teenage sons weren’t living with him, especially as William was living just eight miles away just over the border from his birthplace of Bredwardine.

How could I find out for sure? The 1891 census showed that he was born in 1845 in Bredwardine. So far, I have found several deaths recorded for men named William Preece in Herefordshire during the first decade of the 20th century, but without enough details to be sure any of these record my great-grandfather’s passing.

A very difficult woman

Albert Preece married Celia Millicent Price (yes, another Price family) in July 1922 in Pontardawe in the Swansea Valley. Their only child, my mother Rosemary, was born in July 1928 at the house in Grove Place, Penarth, in which I discovered that Bible in 1981. Grandma was a stylish woman in her younger days, and a talented dress maker. As what follows is less than complimentary, I should say that my love of reading began when she gave me a copy of Enid Blyton’s Secret Island book as a present when I was around seven. I also enjoyed listening to her singing along to the old Welsh language hymns on the BBC television programme Dechrau Canu, Dechrau Canmol. (This Welsh language programme was the inspiration for the English equivalent Songs of Praise.)

At Mum’s funeral in 2018, Dad asked me not to mention in the eulogy that Celia (Mum’s mother) was a very difficult woman. ‘There are still people in Penarth who remember her who may be upset.’ That seemed unlikely, given Mum herself was 90 when she died, but I respected his wishes. Seven years later, I can spill the beans.

When Mum and Dad were newly married in the 1950s, Celia made life really awkward for them. If they came back to Grove Place from the cinema five minutes later than expected she’d refuse to speak to them for a day or so. Mum and Dad once took Mum’s parents on a motoring holiday to Austria. I can only imagine the stress of sharing a small car for two weeks with Celia. Sure enough, a massive falling out followed the return home; my lovely Grampy was not strong enough to get his wife to behave reasonably. These rifts became more frequent after my grandfather died just before Christmas 1966, and we’d go for months and longer not seeing her because of the latest explosion. Reconciliation – such as it was – would typically be prompted by a call from Cardiff Royal Infirmary telling Mum that her mother had had a fall.

Above: my sister Beverley and Grampy in the garden at 15 Grove Place, Penarth, mid 1960s. The conservatory on the right of the house was attached to the middle room in which I found the Bible. The lean-to behind Beverley and Grampy contained an outside toilet, a coal store and the very sparse kitchen.

That old house was always cold. It had fireplaces in every room, including the bedrooms, but after Grampy died they were never used. I vividly remember our only Christmas staying there, in 1967, the first after Grampy died, and the all-pervading cold. My poor father was ill in bed with flu – trying desperately to keep warm.

As a teenager, I used to go with Dad to collect Grandma to bring her to our house in Cardiff for lunch. Even spending ten minutes there while she put on her old, stylish coat would be enough for me to feel an icy chill racing through my body. A couple of years before Grandma died, during the freezing winter of discontent of 1978/79, Mum persuaded her to buy a gas fire to heat the one living room she used. We helped her choose the appliance in the Wales Gas showroom in Penarth. A few days later, we heard that she’d cancelled the order.

Grandma was obsessed with saving money. We once found dozens of packets of rancid butter on the sideboard in her kitchen: she’d found butter reduced in price, and bought them without any concern that she’d never eat that them. She used money that would have been better spent on heating to invest in local government bonds. When she died, we found she’d left all her money to my sister Beverley, who very kindly split it between herself, Mum and me. I will always be grateful to my sister for her determination to do the right thing.

Looking back, it seems clear that Grandma had some kind of personality disorder or other mental illness that caused her to inflict misery on family and friends.

Grandma Celia died on 5 July 1981. We hosted the wake in our garden in Lakeside, Cardiff, including members of Mum’s family that I’d never met before. It was striking how the Welsh and English speaking members of the clan kept largely to themselves. Later, when everyone had left, and the summer evening sun was setting, Mum said quietly, ‘I’m an orphan now’. She always regretted that her lovely father was the parent taken too soon, and although she and Dad spend the final 21 years of her life living in Penarth, Mum always felt her time in Penarth was overshadowed by painful memories of her malevolent mother.

Don’t leave your family history until it’s too late

This family history is inevitably full of gaps, including the identify of ‘C Preece’, the writer of the Goldfields letter. (Was he my Grampy’s uncle?) I am sure Mum must have talked to me about her family history, but because of the very difficult relationship with her mother I naturally took far more interest in my father’s family story, and forgot almost everything about hers. I will try to fill in the gaps to the extent that public records allow. But sadly the human stories that bring a family’s history to life are lost forever. Don’t make my mistake: record the memories of your grandparents and parents while they are still here to tell their stories.

Pingback: 20 years as a blogger | Ertblog