The wonderful finale of the BBC’s hit comedy Gavin & Stacey on Christmas Day brought further fame to Barry in South Wales. It’s a place that has a place in my heart thanks to family seaside memories and visits to its long-gone scrapyard for old steam locomotives.

Last weekend, I took my son Owen for a short break in my hometown, Cardiff. As the rest of the country shivered under blizzards or sheltered from the icy rain, we made the short trip to Barry Island, and were rewarding with a few minutes of glorious winter sunshine. When I was at school, I regularly took the train from Heath High Level in Cardiff to Barry Island, and our Sunday visit brought so many memories flooding back.

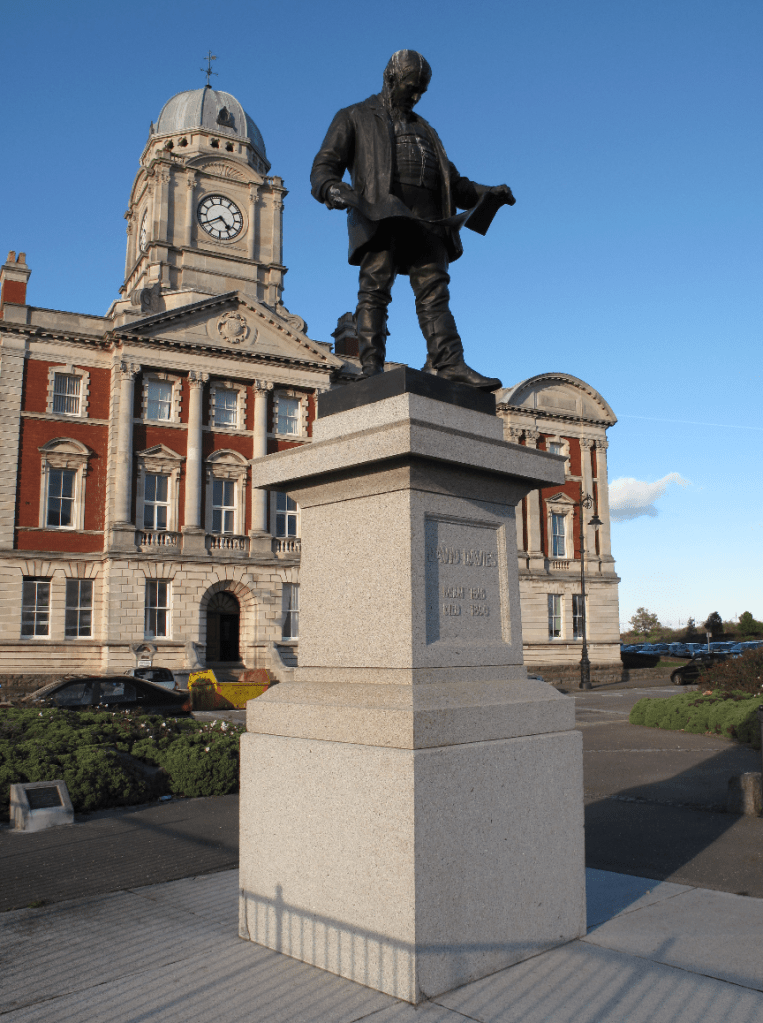

Barry is a town that saw explosive growth during the later stages of the industrial revolution. Barely a hundred people lived there in the middle of the 19th century, but the entrepreneur David Davies of Llandinam saw its potential as a port. Davies was known as Davies the Ocean after the coal mining company that made his fortune. Like many Welsh coal tycoons, he was frustrated by the delays and cost involved in exporting their black gold from Cardiff, and vowed to create a rival port less than nine miles away at Barry. As he exclaimed, “We have five million tons of coal and can fill a thundering good dock the first day we open it!”

Within 30 years Barry overtook Cardiff to become the world’s greatest coal exporting port. Quite a feat given Cardiff was the world’s busiest port for exports in the 1890s. This audacious success was made possible by the new Barry Railway. As I wrote in my blogpost about Penrhos Junction:

At the start of the 20th century, the Barry Railway set off on an outrageous, audacious venture to steal traffic from its earlier rivals. It blew vast sums on a line that soared against the grain of the South Wales landscape. Its new line spanned spectacular viaducts across the Taff and Rhymney valleys to join the Brecon & Merthyr Railway opposite Llanbradach. The expensive line was closed by the Great Western Railway, which absorbed the Welsh railways exactly a century ago, and the great viaducts demolished in 1937.

Barry Island – a seaside mecca

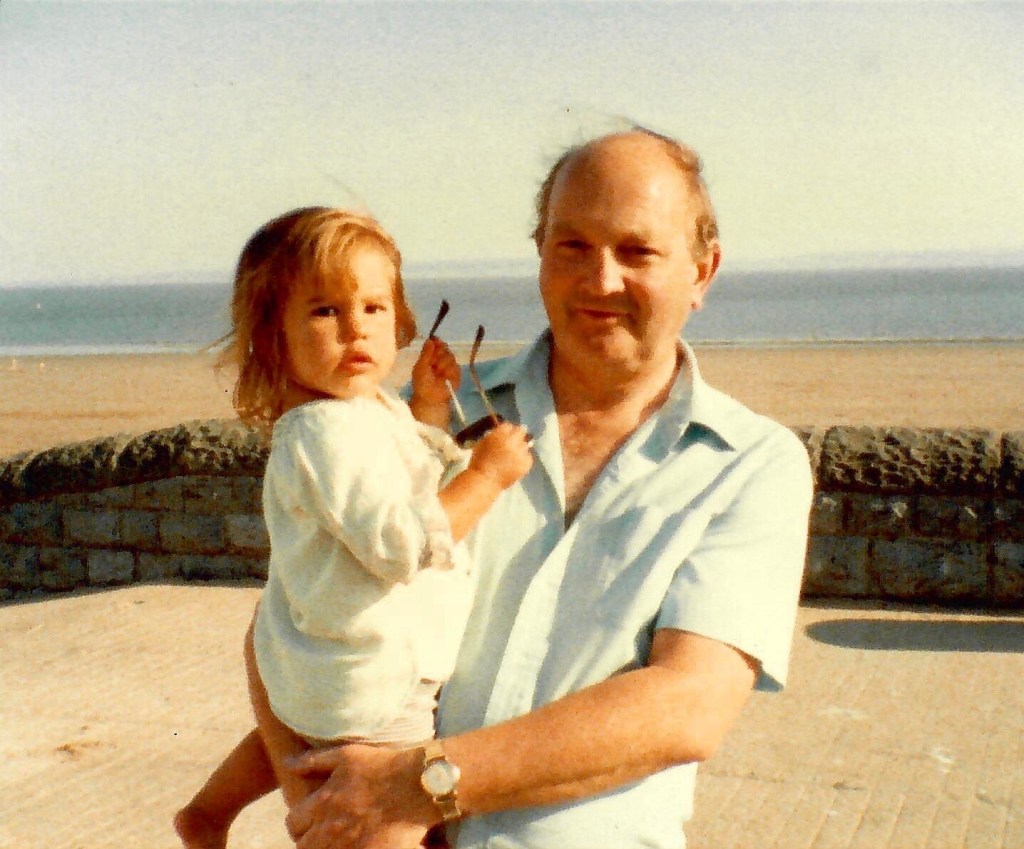

These photos give a clue why Barry Island has such a place in my heart. They were taken during my final university summer break, in July 1984. Dad, then aged 57, is carrying his granddaughter Ria, aged one, while I am pictured making a sandcastle with Ria and my sister Boo (Beverley). That year was the second heatwave summer in a row, making Barry an obvious destination.

The pleasure park with its rides was the other family attraction, and here I am about to descend the log flume with niece Siân, then aged three. We had more fun than the following year, when my Dad suggested I take Siân into the haunted house, which she found terrifying…

We went to Barry in all seasons. This is October 1985, with the old Butlins resort dominating the hill to the east of Barry Island in the photo to the left. Dad was always amazed that Butlins got permission to build its resort here in the 1960s, given it put popular Nell’s Point out of bounds to anyone not staying at Butlins. Barry was the last Butlins to open, in 1966, and after years of decline it closed in 1996, just as the budget airline era was beginning.

Barry: steam’s graveyard

For me, Barry had another, unique attraction. While you could find funfairs and sandy beaches at countless seaside towns, only at Barry could you climb over old steam locomotives. This was Dai Woodham’s famous Barry scrapyard. When British Railways got rid of its steam engines with indecent haste in the 1960s, Woodham bought hundreds of them for his scrapyard in Barry. He wasn’t alone, but unlike his rivals Dai decided not to cut them up, concentrating on easier to scrap rails and wagons.

This is the earliest photo I can find of a visit to Barry scrapyard, showing me aged 15 on the footplate of a handsome LMS 4F freight engine. 4123 is 100 years old this year, and being restored by the LMS Society. Its website gives the history of the locomotive here.

It’s amazing to think that as teenagers we could walk into a scrapyard of rusting steam engines without any restrictions. I’m not sure I’d choose to have a picnic on an abandoned heavy freight engine today, as I did on this GWR 2-8-0T tank engine, 4270, in July 1983.

I’ve written in more detail about Barry scrapyard here. Over 213 engine were saved, with the last being removed in 1990.

Barry: a town transformed

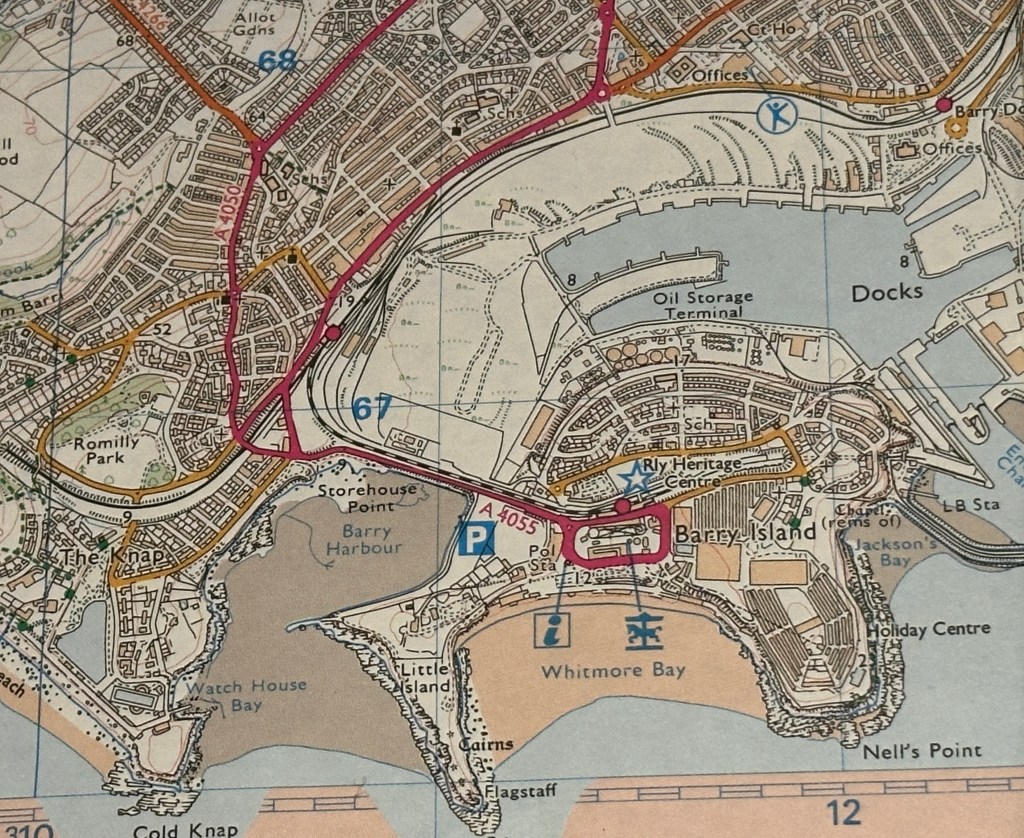

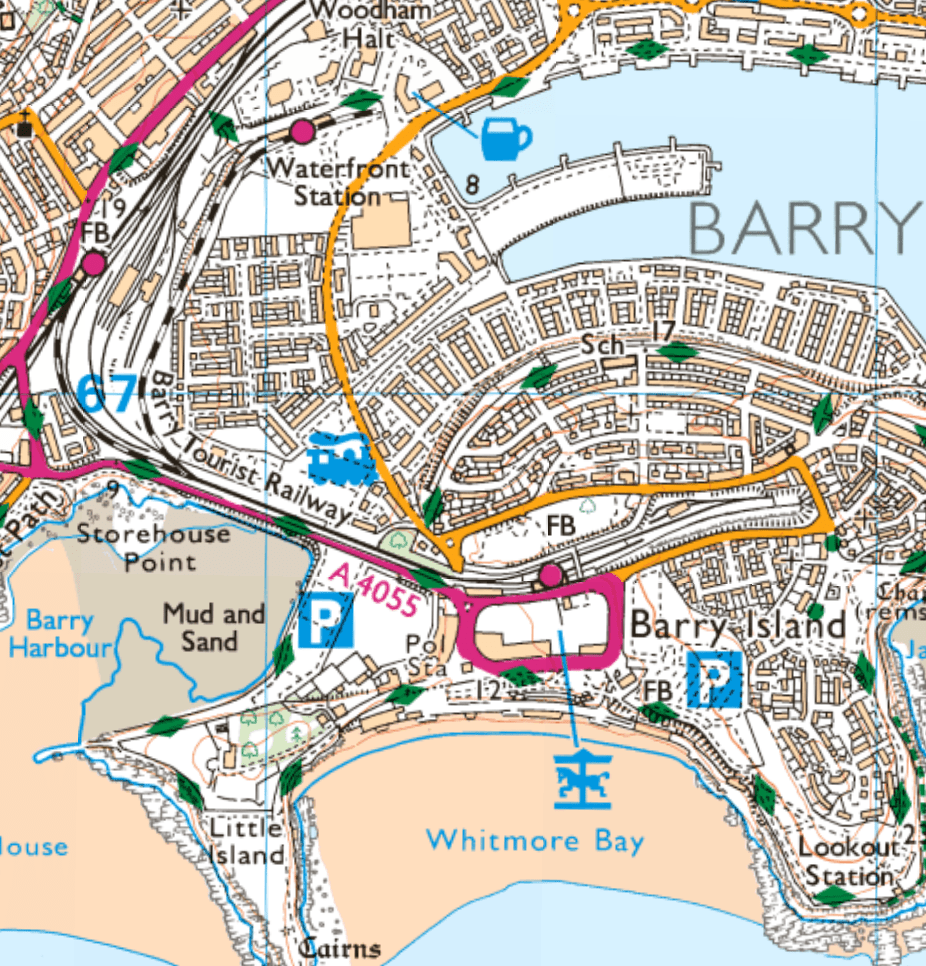

This 1985 photo shows the town of Barry behind one of Dai Woodham’s rusting steam engines. You can see how derelict this part of Barry was then – yet a few decades earlier this would have been a web of railway sidings near Barry docks and Island. Today, the landscape has been transformed, with the huge, empty space between Barry Island and Barry Town filled with new houses and supermarkets. Much as I miss the chance to clamber over old steam engines, I have to admit today’s Barry is more attractive. The contrasting maps below (1998, left, and 2024, right) graphically show how the area has changed – just look at that empty land north of the causeway to the island in the 1998 version.

But it’s not an island!

No, Barry Island isn’t an island. It was originally, before David Davies decided this would be the perfect place for a major port. The causeway that carries the main road and railway turned it into a peninsula. But the name lives on. I’m sure that Barry will also continue trading on its Gavin & Stacey fame long after the Christmas Day finale…

Pingback: Headlines from my 50 year old childhood scrapbook | Ertblog