Above: shades of the 1930s. My copy of the Guardian reporting over 3 million out of work, January 1982

I can’t be sure when I first read the Guardian. So the headline of this post is rather more definitive than the evidence justifies. Thanks to his job running PR for the old South Glamorgan county council in Cardiff, my father brought a stack of papers home each day, including the Guardian, South Wales Echo and Western Mail. I vividly remember announcing, rather awkwardly, one evening that I would start reading the papers, as well as calling my parents Mum and Dad, rather than Mummy and Daddy. This declaration was some time before I went to Cardiff High School aged 11 in September 1975. So let’s take that as evidence enough.

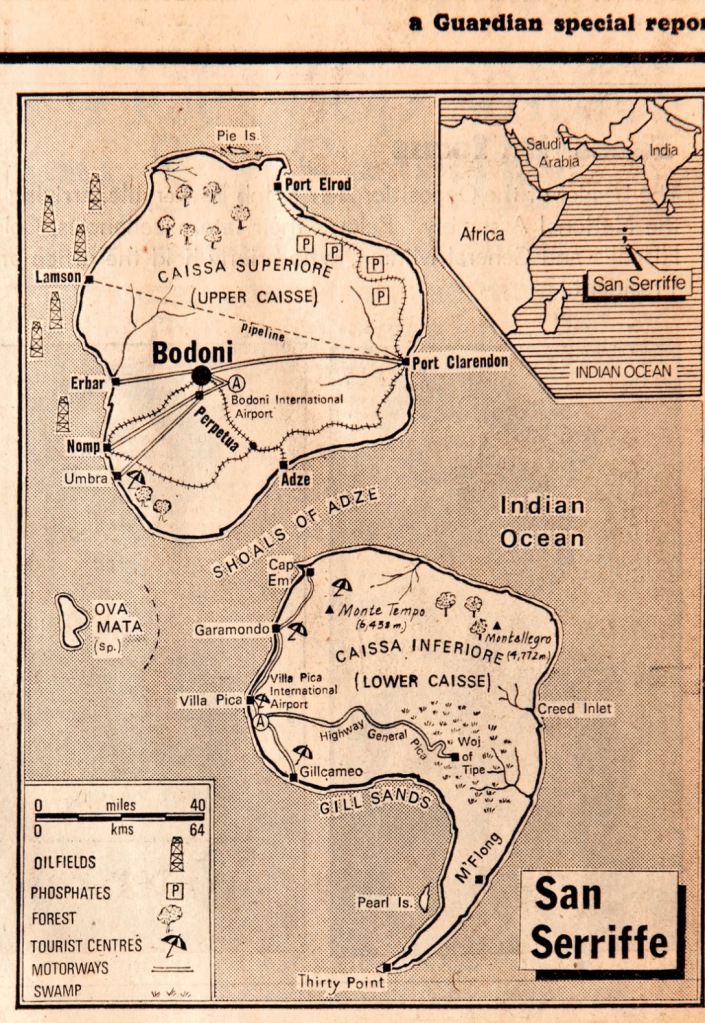

One of my favourite early Guardian memories was the famous San Serriffe April fool of 1977. This spoof was the newspaper equivalent of the BBC’s famous 1957 Panorama spoof story about the year’s bumper crop from Switzerland’s spaghetti trees. I remember poring over the Guardian’s seven page travel supplement about the tropical islands of San Serriffe. As the paper explained in 2012, everything connected with San Serriffe was named after printing and typesetting terms.

The Guardian is famous as a writers’ paper. Matthew Engel, a fine writer on cricket and much more, once noted how the paper allowed its journalists to retain their intellectual freedom, unlike those on other titles. As a student I enjoyed reading an even more famous Guardian cricket writer, John Arlott, whose weekly wine column introduced me to Rioja.

The history makers

Over 30 years ago, I bought Changing Faces, Geoffrey Taylor’s fine history of the Guardian from 1956 to 1988. At the time, 1993, it seemed to cover a uniquely dramatic period, including the painful (for many) dropping of Manchester from the paper’s title, and its move to London. Yet the years from 1988 have been even more transformative, with the Guardian’s move from a print title to a multimedia media organisation. Ian Mayes has recorded the story of those years in the latest volume of the Guardian’s history, called Witness in a Time of Turmoil – a title that surely hints at his ringside seat as a Guardian writer and executive during those events. Reading Mayes’ book was an exercise in nostalgia, especially the earlier chapters replaying some of the events leading up to 1986, including the trauma of the Guardian’s role in the jailing (or gaoling as the 1980s paper would have said) of Sarah Tisdall.

In the early 1980s, the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the West, led by the United States, was intensifying. The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament was revived, with huge crowds in Britain protesting against the arrival of America’s cruise nuclear missiles at the RAF base at Greenham Common. The great question was when those weapons would arrive – and the Guardian had the answer, thanks to Sarah Tisdall, a 23 year old junior clerk at the British Foreign Office.

Tisdal had come across a confidential memo from defence secretary Michael Heseltine to the prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, about the precise timing of the arrival of the missiles. She anonymously delivered this and another document to the Guardian. The government secured a court order to demand the paper hand back the documents, which enabled it to identify Tisdall as the source. She was found guilty of under the Official Secrets Act and sent to prison for six months.

The Guardian’s editor, Peter Preston, was horrified that the paper had played a key role in her fate, when the paper itself wasn’t prosecuted. He chastised himself for years afterwards for the disastrous misjudgment of not destroying the documents after the paper published its scoop. An even bigger mistake was publishing the whole text under the heading, ‘Heseltine memo to Thatcher on cruise timing’. This made it obvious that the story was based on the memo leaked by Tisdall, rather than other government sources.

The Tisdall case exploded during my second year as a law student at Leicester university. By coincidence, I was studying civil liberties law that year, including the Official Secrets Acts. Sarah Tisdall was charged under the heavily criticised section 2 of the 1911 Act, which was a ‘catch all’ that made it a criminal offence to disclose any official information without lawful authority. (Theoretically, she could have been charged for telling her mother that the Foreign Office stationery cupboard had run out of pencils.)

The Guardian ran a powerful leader after Tisdall was jailed condemning her savage sentence, and highlighting how the prosecution changed the thrust of its case, from the gravity of the implications for national security to the embarrassment caused to the Thatcher government. The paper also underlined the hypocrisy of prosecuting a junior clerk but not the Guardian, almost certainly because the paper would most likely have been found not guilty as publication was in the public interest: everyone knew that the cruise missiles would be deployed, but the government had deliberately not said when, to make it harder for protesters to gather.

Peter Preston in 2005 recalled that the Guardian almost won an appeal against the demand it handed over the documents. The Court of Appeal conceded that the documents were harmless, but refused to overturn the disclosure order on the grounds that ‘the sort of unreliable public servant who had leaked it might leak something more dangerous next time’. On the same grounds, someone who nicked 50p of sweets might later rob a bank, so should receive a punitive sentence. Preston took a bitter lesson from his handling of the Tisdall case: ‘If a source needs protection, if you have given your word, then don’t call for a solicitor – because due process will drag you down’.

The end of hot metal – and the renaissance of the British press

Buying a newspaper was a lottery in the early 1980s. I never knew when I walked into the newsagent’s shop whether the Guardian had appeared that day. (If it had, I’d find photos printed so badly that I often couldn’t identify the subject.) The blame lay with the print unions and cowardly newspaper bosses. Printed newspapers are perishable goods – no one wants to buy yesterday’s paper – and the print unions used this to blackmail management to concede countless ridiculous demands rather than lose that day’s paper. By 1986, it had been possible for over a decade for journalists to type their stories directly into the system for printing, but the print unions insisted that only their members were allowed to do so. If a Guardian reporter had touched a keyboard, the print workers would have walked out, leaving me without a copy at the newsagents. It was a protection racket.

Liberation came when Rupert Murdoch secretly moved his papers overnight to Wapping in London in January 1986, where they could be produced and printed using new technology that the unions had blocked for years. (The previous owner of the Times and Sunday Times, Roy Thompson, had closed the papers for a year in 1978-79 to try to force the issue, but failed, selling to Murdoch in 1981.) ‘Fortress Wapping’ was the scene of ugly fighting between print workers and the police for almost a year. Murdoch had broken the grip of the print unions, and his rivals benefitted as much as he did. It’s no coincidence that the years following saw the birth of several new national papers, notably the Independent (October 1986), Sunday Correspondent (1989) and Independent on Sunday (1990). The ‘dirty digger’ had transformed the economics of newspaper publishing.

The Independent was created by a group of Daily Telegraph journalists, and seemed more of a threat to their former paper than to the Guardian. But as the Eighties drew to a close, the sales gap between the Guardian and its newer rival closed, especially after the Indy launched its brilliant Saturday supplement in the late 1980s. It was the perfect Saturday morning read, and for the only time in my adult life I was lured from the Guardian for the pleasure of its Saturday edition. The Guardian learned the lesson, and recognising the potential of Saturday in an era when that day’s edition was typically the worst selling of the week. It launched its Weekend magazine – at first as a low cost print effort, upgraded to a glossy magazine in 2001. I tell the story of that magazine here.

The Grauniad

The Guardian was once so famous for its misprints that it was affectionately called the Grauniad, supposedly because it once misspelt its own name. Even when the Guardian mocked the spelling mistakes of others, it discovered that it was itself responsible for the errors:

‘An item headed Bad Day: Educashun … derived mild amusement from numerous spelling mistakes in a Labour Party jobs advertisement carried in the previous day’s paper. All the errors were, in fact, made by The Guardian. None of them was in the original copy supplies by the Labour Party.’ (January 1998)

This correction appeared in Corrections & Clarifications, a daily column in which the Guardian made amends for the errors that are inevitable in the frenetic process of publishing a daily (and now online) paper. The Guardian appointed Ian Mayes as Britain’s first readers’ editor (or ombudsman) in 1997, following the example of the Washington Post. The intention was to build trust with readers – and those who appeared in the paper’s reporting – through a commitment to accuracy.

Many of the corrections are very amusing. One of my favourites recalled the Guardian’s north western roots:

‘A Country Diary .. was headed Heald Green, Cheshire. Heald Green is in Stockport, Greater Manchester. The error was caused by nostalgia.’ February 1998

The final correction seems to sum up the character of the Guardian:

‘The absence of corrections yesterday was due to a technical hitch rather than any sudden onset of accuracy’. January 1999