A mighty transatlantic battle is in prospect over how to regulate artificial intelligence (AI). Donald Trump’s second administration seems sure to opt for the lightest of light touches, influenced by tech tycoon Elon Musk. (If Musk can tear himself away from his bizarre obsession with Britain.) The European Union has already legislated for a far more restrictive approach, with Britain likely to follow a middle way. The sensible aim must be to unleash the creative, social and economic benefits of AI while minimising the harm it may cause if abused or badly handled.

As debate raged about AI regulation, it struck me that many of the arguments deployed for and against AI and tech regulation also played a huge role in shaping the response to the railway revolution in the 19th century.

The railway age properly began in September 1825 with the opening of the world’s first public railway to use steam locomotives, the Stockton & Darlington Railway in County Durham in the north of England. After the success of the first intercity railway between Liverpool and Manchester, opened in 1830, Britain enjoyed a railway boom, as pioneers planned lines linking major cities – and serving industry, the original purpose of the iron road. By the early 1840s, railway mania had taken over, in a prelude to the dot.com boom at the turn of the 21st century. In 1844, 240 private bills were presented to the British parliament to authorise 2,820 miles of railway. Had all these been built, the £100 million of capital needed represented over one and a half times Britain’s gross domestic product (GDP) for that year. Parliament still approved half these railways.

Anything goes? The heyday of the laissez-fair state

Britain in the 1840s was a firmly non-interventionist state. The dominant philosophy was laissez-faire: small government, low taxes and the free market. Most acts of parliament were private acts to authorise new railways rather than government initiatives. Anyone able to raise money could form a railway company and apply to parliament for permission to build their pet route. The sheer volume of railway business threatened to overwhelm the Westminster legislature. But an attempt to create order by setting up a railway advisory board to vet proposed plans before they reached parliament was short lived, killed by the powerful railway lobby. (And conflicts of interest: 157 out of 658 MPs had financial interests in the railways.) This was Britain’s last chance to create a strategic rail network, deploying investors’ money more efficiently. The failure led to many investors losing most if not all their money on rail schemes that had no hope of success, again pre-empting the dot.com bubble of 1999-2000.

Despite this backdrop, Britain’s governments were surprisingly interventionist by the standards of the era. As early as 1840, legislation required all new railways to be inspected before opening by inspectors from the newly formed railway department of the Board of Trade. This department began life with just three employees: an engineer, a statistician and a lawyer. (A mix of expertise that seems curiously modern.)

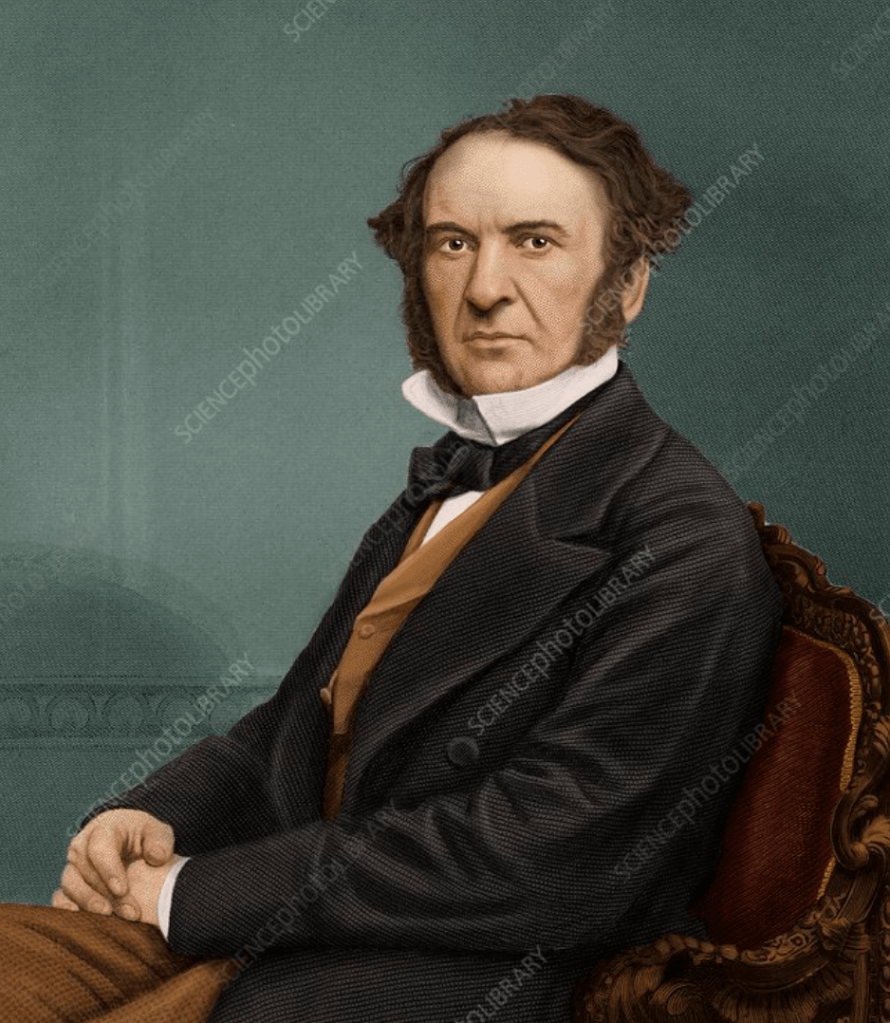

Four years later came the legislation that some regard as the dawn of state regulation. A talented politician and future prime minister, William Gladstone, piloted the Railway Regulation Act, which had a profound affect on British railways for over a century. Gladstone believed in free markets, but also accepted that sometimes governments should intervene to achieve a greater good. The act set minimum standards for passenger trains, with at least one train a day open to the cheapest fares, which were set at one old penny a mile. These third class passengers should have seats protected from the weather – in 1844, it was common for these poor people to be carried in open wagons in all weathers. These cheap trains became known as parliamentary (or parly) trains, and led to a boom in third class train travel, from 40 million journeys in 1851 to 1.2 billion in 1911. (Incidentally, second class was later abolished on most British trains, and third class became the new second class, eventually being renamed standard class in 1987.) The term parliamentary train lives on, although its meaning has changed to apply to a minimal train service run to avoid the rail company going through a formal closure of the line.

Another major intervention came in 1846, when parliament set a standard gauge (the width between the rails) of 4 feet 8 ½ inches in Great Britain and 5 feet 3 inches in Ireland. This was prompted by a clash of titans: the father of the railway, George Stephenson, who used the standard gauge for his railways because it was the norm in the colliery lines of his native Northumberland, and Isambard Kingdom Brunel, who chose the wider gauge for the Great Western Railway from London to Bristol. Brunel was right that a wider gauge had many benefits – especially more spacious trains – but didn’t realise that even by 1835 the narrower gauge had won the day, and there was no room for two gauges on a national network. Parliament acted after complaints at the chaos at Gloucester where goods and passengers had to transfer between broad and standard gauge trains. The 1846 act didn’t abolish the broad gauge outright – Brunel’s legacy survived until 1892 – but it did ensure its demise.

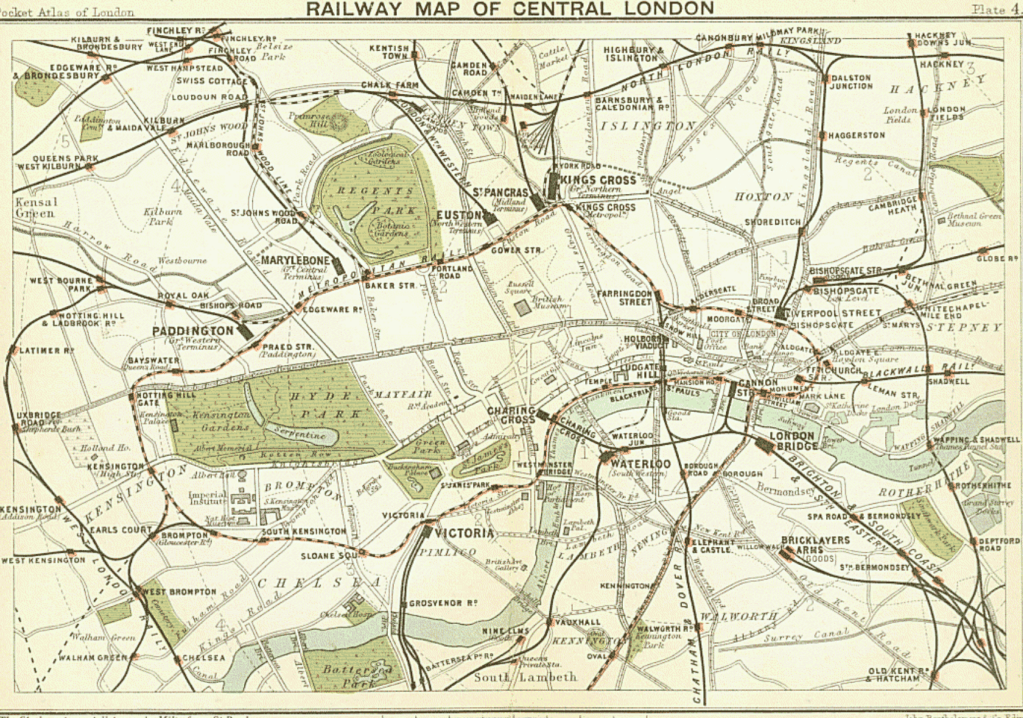

London’s termini – a rare example of strategic railway planning

As I blogged recently, London is an unusual example of government planning intervention to shape Britain’s railway map. Sir Robert Peel appointed a royal commission to look at the location of new London rail termini, which reported its recommendations within an astonishing three months of his announcement. While the commissioners’ recommendations weren’t mandatory, they were generally respected, which is why Marylebone, St Pancras and Kings Cross are all north of the Marylebone and Euston roads. This saved thousands of homes and properties from destruction, even though to this day people arriving in London have to transfer to crowded underground trains to reach the West End.

Safety: the great regulatory failure

The greatest regulatory failure in the first century of British and Irish railways was safety. Even the man who led the railway inspectorate in the 1870s, Captain HW Tyler, insisted that responsibility for safety must rest with the individuals and companies concerned. Any form of direct government supervision, he contended, would be harmful because it would weaken and divide responsibility. He maintained this view even while his safety recommendations in disaster investigation reports were repeatedly ignored by the powerful rail companies, such as the London & North Western.

Parliament finally accepted responsibility for improving safety as a result of the appalling disaster at Armagh in Ireland in 1889. Eighty people died, many of them children, when a train on a Sunday school outing ran out of control and collided with another train on a steep hill. The tragedy, the worst in Irish rail history, would not have happened had trains been required to have continuous automatic brakes. (The ill-fated train had brakes that stopped working when disconnected, rather than modern brakes that are applied when this happens.) Parliament quickly passed the Regulation of Railways Act 1889, which made effective brakes compulsory, as well as the block signalling system that prevents two trains entering the same section of track. The act also gave powers to rail companies to prosecute passengers who don’t have a ticket – a provision that is still in force today and which has recently been abused by Northern Trains.

20th century failures

While Armagh resulted in safer trains, the 20th century saw another lengthy battle to save lives by avoiding trains going past signals at danger. In 1906, the Great Western Railway introduced automatic train control, which stopped a train if the driver passed the initial signal showing the next signal was showing stop. Within two years, the GWR had applied ATC to all its main lines. Yet other railways refused to follow its admirable example, and thousands of lives were lost in the following decades, despite accident inspectors recommending ATC. For example, following the Charfield disaster in Gloucestershire in 1928 the inspecting official, Colonel Pringle, recommended the adoption of ATC ‘which can alone prevent accidents of this kind’. Yet It took the shocking Harrow & Wealdstone and Lewisham disasters of the 1950s before the (by then nationalised) British Railways belatedly introduced a national automatic warning system.

Lessons for AI and tech regulation

As we have seen, for a firmly laissez-fair, small government state, Britain in the 19th century proved surprisingly interventionist in response to the railway revolution. But those interventions were, with a few exceptions such as legislating for a common gauge, tactical and not strategic. The power of the rail companies – comparable to today’s Silicon Valley barons such as Musk and Zuckerberg – discouraged any more strategic approach to building a national railway network. That approach was consistent with the powerful laissez-faire philosophy that dominated British political leaders in the first half of the 19th century.

LTC Rolt, the great railway historian who died in 1974, wrote in Red for Danger:

History of railway legislation shows that safety measures have only been imposed by legal compulsion when persuasion had already caused the desired reform to be almost universally adopted.

This is astonishing but largely true. Armagh in 1889 was an example of people dying on one of the few railways yet to adopt modern safety measures. Parliament legislated to force the stragglers into line. As we have seen above, Rolt also saw danger in governments overriding the responsibility of individual companies. In other spheres, we can see there’s some merit in this argument: historians of the 2007/08 financial crisis think the fact regulation of Britain’s enormous financial services industry was split between three regulators explains in part why that crisis hit the UK so badly.

The world is a very different place compared with 19th century Britain. Government intervention is far more common, and even expected, although the political right has campaigned for years for a smaller state. Soundbites such as ‘health and safety gone mad’ are commonly deployed especially in the tabloid media and social media. (Small state enthusiasts are much slower to explain which life-saving measures they would axe.)

But governments must tread with care, balancing often conflicting objectives. At a time when many western countries are seeing limited economic growth, their governments want to harness the potential of Artificial Intelligence to boost their economies and improve how services are delivered. Much as the railways changed 19th century Britain, AI could be transformative. But how do you legislate to minimise the risks that come with AI – the equivalent of the appalling safety record of Victorian British railways?

The European Union was quick to act, with its AI Act. Critics say that the act oversteps the mark, with potentially ‘catastrophic implications for European competitiveness’ in the words of one of the signatories to a letter from 150 European businesses to the EU. France’s president Macron reflected, ‘We can decide to regulate much faster and much stronger than our major competitors. But we will regulate things that we will no longer produce or invent. This is never a good idea.’ Policymakers need to avoid regulation that makes life harder for users than necessary – such as the inflexible cookie warnings that infuriated us for years after the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) came into effect in 2018. (I should acknowledge that many websites took the strictest interpretation of the rules, which didn’t help.)

The other major change is that Britain in the 1840s didn’t have to worry about what other countries thought. It was the world’s dominant power. By contrast, the UK, EU and other major players have to consider the implications of their actions on other nations, especially the United States under Donald Trump. An aggressively protectionist American government is likely to punish countries it sees as restricting its Silicon Valley technology giants, who dominate the world stage. You only have to look at Elon Musk’s increasingly bizarre but sinister war against the British government to see where this might go. That’s not to say that governments should abandon the interests of their people – just that they need to act intelligently.

The power of ‘something must be done’

Governments often act when under pressure from the media, lobby groups and citizens. That was true in the 19th century: laissez-faire governments intervened when they recognised something had to be done, whether about the chaos of having a rail network with two conflicting gauges or preventing scores of children being crushed to death in a train crash on an Irish hillside. It’s much the same today. The latest Wallace and Gromit film Vengeance Most Fowl captured a common fear of AI being abused, with a criminal penguin hacking into Wallace’s helpful robots, causing chaos as they go rogue. It’s easy to see real life AI failures and abuses prompting calls for action.

Final thoughts

LTC Rolt described a 20th century British railway carriage as one of the safest places on earth. As we have seen, it wasn’t always the case, and the reluctance of politicians to intervene undoubtedly cost lives. But they did create a climate of extraordinary innovation and enterprise, which created a national rail network in an amazingly short time. AI offers similar transformative opportunities, and legislators could usefully learn from Victorian Britain’s experience as they decide how to maximise the benefits and minimise the risks of the AI revolution.

Pingback: Why London’s rail termini are so far from the centre | Ertblog