I’ve been dreaming of cycling across mysterious Romney Marsh to historic Rye for years. The inspiration was Jack Thurston’s first Lost Lanes book of bike tours, along with childhood memories of Malcolm Saville’s adventure stories for children based there. (More on that later.)

I finally followed Jack’s tour in September, and have made a documentary video about it. Unusually for my videos, this focuses less on cycling and more on the fascinating history of this corner of England. This blogpost tells the story of my ride, along with a longer version of the stories from the past featured in the video.

Here’s the video on YouTube. (Do please like and subscribe!)

Britain’s most spectacular railway station

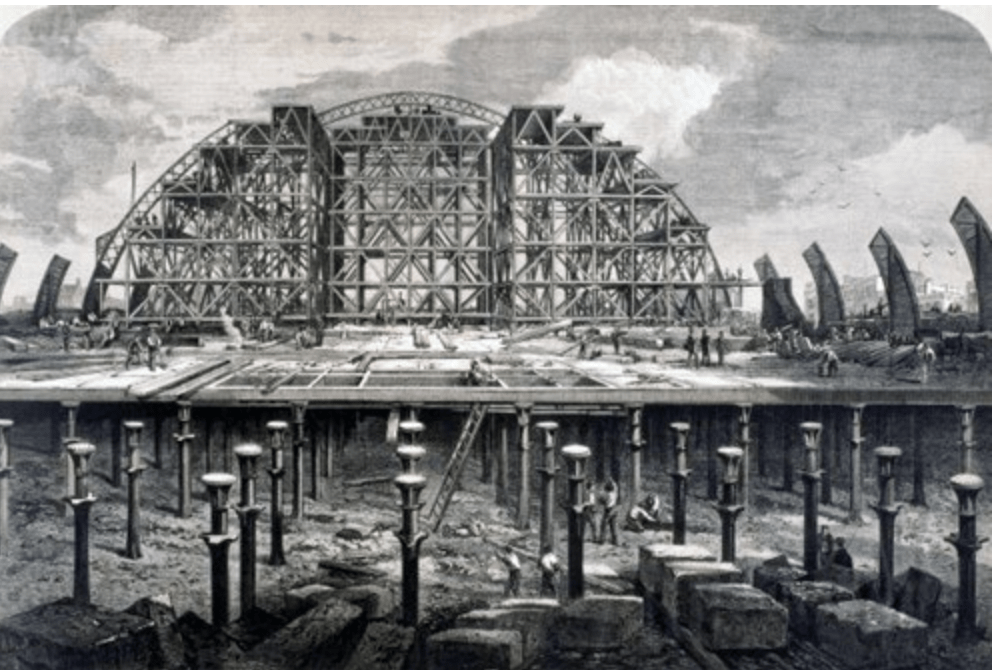

My journey began at St Pancras station in London, Britain’s most spectacular railway station. When the Midland Railway decided it needed its own London terminus, it chose the most opulent neo-Gothic style for the station building, along with a stunning roof that spanned all the platforms. It overshadowed its neighbour, Kings Cross station, although the simpler lines of the older station have arguably stood the test of time better.

St Pancras station was built on beer – almost literally. The spectacular roof had a very practical purpose. It allowed the undercroft – or basement – to be used to store barrels of beer from England’s brewing capital, Burton on Trent. The pillars holding up the platforms and tracks were spaced to allow barrels to be kept between them. In later years, after the beer traffic switched to the roads, it was used as a car park. Since St Pancras’s renaissance as the international terminal for trains to Paris and Brussels, you can find a host of shops and cafes here. The reconstruction made the undercroft far lighter by removing a large section of the old roof no longer needed to support the old western platforms.

It’s said that in Victorian times people used to mistake St Pancras station for a cathedral. The story goes that American visitors would ask for the times of services, only to be baffled to be given times of trains to Leicester and Manchester. The tale is too good to be true, but St Pancras is a cathedral of the steam era. As late as the 1970s, you could catch a train to Scotland from this glorious terminus. After years of neglect, in 2007 it hosted cross-border trains for the first time in 40 years – to Paris and Brussels via the High Speed 1 line and the Channel Tunnel.

Saving St Pancras: John Betjeman to the rescue

This is the lost glory of the old Euston station, destroyed in the early 1960s to create today’s soulless terminus. The destruction of the Euston Arch and Great Hall, despite pleas for their survival, swept aside by prime minister Harold Macmillan, caused an outcry. (In truth, much of the old Euston was undistinguished, but a look at the space between the 1960s monstrosity and the Euston Road shows there was plenty of room to relocate the historic arch. Its counterpart at Birmingham Curzon Street has survived to feature in the new Birmingham High Speed 2 station, now being built.)

St Pancras was threatened with a similar fate to old Euston, as British Railways planned a new joint St Pancras and Kings Cross terminus in the 1960s. (I shudder to think how awful that would have been.) But a campaign featuring the poet John Betjeman saved the day, mobilising the anger at the loss of the Euston Arch.

Betjeman was a champion of Britain’s heritage. He popularised Metroland – the Home Counties suburbia created by the Metropolitan Railway a century ago – for a new generation through his writing and television programmes. I still cherish his book about London’s historic railway stations, which featured evocative black and white photos of the city’s termini. His joyous statue at St Pancras, celebrates this much loved poet laureate.

When I was at university in Leicester, I took the train a few times into St Pancras, and in those days the InterCity 125 high speed (something of a misnomer on the Midland main line) train arrived under Barlow’s stunning roof at St Pancras. Trains for the Midlands today have their own outpost at St Pancras, freeing the great arch for Eurostar and high speed services to Kent

The old Midland Grand Hotel of 1873 has been reborn as the St Pancras Renaissance Hotel. The original hotel was one of the most celebrated in London when it opened, but its design flaws became increasingly fatal as the 20th century dawned. There were just nine bathrooms for its 250 bedrooms and no central heating, so visitors chose better equipped, newer hotels. By the 1930s, the game was up, and the LMS, which took over the Midland in 1923, converted the Midland Grand into offices in 1935. By the later 1980s, the building was abandoned and derelict. Against all the odds, the St Pancras Renaissance has risen from the cobwebbed, vandalised shell.

Thomas Hardy and the bodies in the graveyard

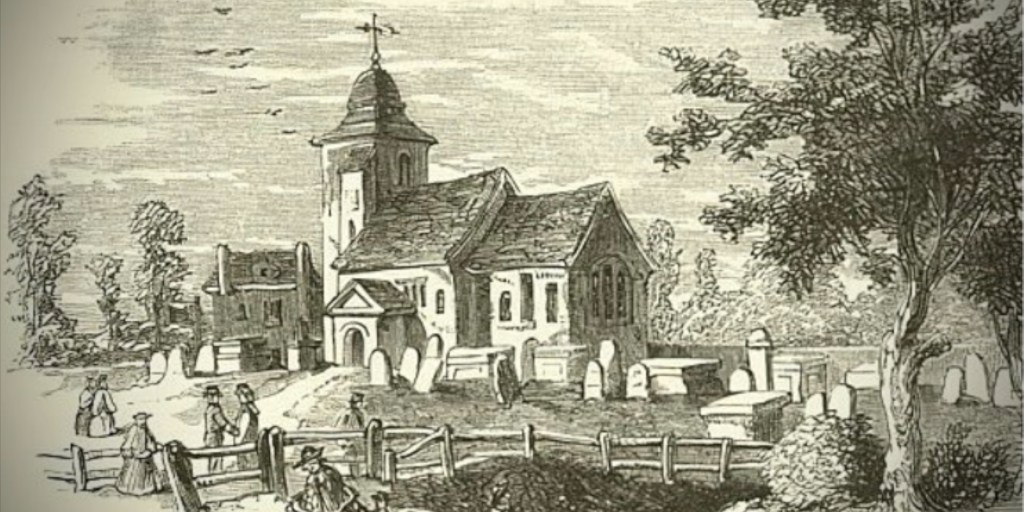

Thomas Hardy is famous as a novelist and poet who made Wessex famous. But he had a little known, and gruesome, role in the creation of St Pancras.

The engineers planning the new Midland terminus had a problem. The route into the new station was blocked by graveyards containing thousands of bodies, including those of refugees who had fled the French Revolution. The exercise to move these human remains had gone disastrously wrong, with human remains strewn across the urban landscape.

Thomas Hardy was a young architect’s assistant and had the unenviable job of making sure that the bodies were respectfully moved and reburied away from the path of the new railway. He never forgot his grim experience, and relived it in his poem, the Levelled Churchyard.

Thomas Hardy – The Levelled Churchyard

“O passenger, pray list and catch

Our sighs and piteous groans,

Half stifled in this jumbled patch

Of wrenched memorial stones!“We late-lamented, resting here,

Are mixed to human jam,

And each to each exclaims in fear,

‘I know not which I am!’“The wicked people have annexed

The verses on the good;

A roaring drunkard sports the text

Teetotal Tommy should!“Where we are huddled none can trace,

And if our names remain,

They pave some path or p-ing place

Where we have never lain!“There’s not a modest maiden elf

But dreads the final Trumpet,

Lest half of her should rise herself,

And half some local strumpet!“From restorations of Thy fane,

From smoothings of Thy sward,

From zealous Churchmen’s pick and plane

Deliver us O Lord! Amen!”

Britain’s fastest train

My journey to Kent was my fastest ever domestic rail trip. My train sped to Ashford at up to 140 miles an hour, travelling along HS1, the Channel Tunnel rail link. It makes a day trip to the garden of England a doddle if you live in or near London.

The only downside? Bikes travel in the coach intended for disabled people, and there wasn’t enough room for both. But the female train manager was a true diplomat, and cyclists and those in wheelchairs were very reasonable in making the best of the situation.

HS2, our second high speed rail line, from London to Birmingham, has been far more controversial, partly because of the usual ‘not in my back yard’ protests, especially here in the Chilterns, but also because of the gross mismanagement of the project by politicians and managers. But one day it will be as much a part of everyday life as HS1 is today.

A watery defence against Napoleon

The Royal Military Canal stretches for 28 miles across Sussex and Kent, roughly following the English Channel coast. I had long assumed that it was built to allow safe inland passage of goods to avoid ships being attacked by the French during the Napoleonic wars.

In reality, this was a third line of defence (after the Royal Navy and coastal defences): the last barrier to any French forces that successfully landed on the English coast. Over a century later, it was reinforced in case of Nazi invasion in 1940, as the machine gun pillbox in the photo above illustrates. By the time the canal was finished, Napoleon was no longer a threat, and the canal has been a tranquil backwater ever since.

The fifth continent

In the early 19th century, Richard Barham was the vicar of St Dunstan’s church in the village of Snargate on Romney Marsh. He declared that there were five continents: Europe, Asia, Africa, America – and Romney Marsh. This declaration indicated how the marsh was a place apart 200 years ago. It still is to some extent, although cycling across the area I was surprised it wasn’t more ‘marsh-like’. The many water channels are obviously effective in draining the ground and making it fertile land for agriculture.

Snargate is more a hamlet than a village, but its traditional pub has become a Romney Marsh institution. It has been run by the same family since 1911, and is lit by a single electric light in each room. (Electricity was apparently only installed in the 1970s.) Its best known landlady, the late Doris Jemison, arrived in Snargate in the 1940s as a land girl, helping keep food production going when the men went to war. Doris died in 2016, but her daughter Kate keeps this gem going. She serves real ale from the barrel, while the pub’s walls are decorated with second world war memorabilia. I could easily imagine Spitfire pilots downing pints here during the Battle of Britain. I was grateful to the landlady (Doris’s daughter) and her customers for allowing me to film short clips for my video after I finished my drink.

Dungeness – a world apart

If Romney Marsh didn’t seem as other-worldly as I expected, Dungeness certainly did. It was a bit of a slog getting there, as a strong headwind had developed as I progressed across the marsh. (At one point I changed direction, and was amazed to be bowling along at 19mph, rather than 12mph!) Dungeness is sometimes called Britain’s only desert, and although the Met Office has rejected this claim it is truly a place apart. Its big skies and isolation have drawn artists including the late filmmaker and gay rights activist Derek Jarman, who made Prospect Cottage his final home in the 1980s. He created a wonderful garden on the shingle beach, which became famous around the world. You can now visit Prospect Cottage, which was saved for the nation in an appeal in 2020.

Historic Rye

It was a joy to spend a night in Rye, one of Britain’s most unspoilt historic towns. It was once an important harbour, one of the famed Cinque Ports that supplied ships to the king in the days before the Royal Navy was created. In medieval times, Rye was a frontier town, just 25 miles from France and vulnerable to French raiders. In 1377 the French destroyed the town and snatched the church bells. The men of Rye sailed across the English Channel to retrieve the stolen booty. Ironically, the town had been a French possession until 1247, when it was handed back to the English crown apart from an area north of the town, which is called Rye Foreign to this day. (I cycled through it on my way back to Ashford, after a steep climb out of Rye.)

Rye was notorious as a smuggling paradise in the middle ages and right up to the early 19th century. Its narrow streets and nooks and crannies were perfect ground for smugglers, who evaded customs duties on goods like wool, cloth and, later, beer, tobacco and tea. According to legend, there was a secret smugglers tunnel between the Mermaid Inn and the Old Bell Inn in the next street. (But legend may be the right word: secret passageways are ubiquitous in tales of the past, and Enid Blyton made good use of them in her Famous Five stories.)

I enjoyed a pre-dinner drink in the Old Bell’s beer garden, making the most of the autumn sunshine. My 46 mile ride had been a slog at times, despite the largely flat landscape, thanks to the headwind, making my half pint very refreshing. I was amused to hear people at nearby tables mourning the loss of sub editors on national newspapers, and the resulting errors.

Malcolm Saville’s Rye

Few people today have heard of Malcolm Saville, but in my 1970s childhood he gave Enid Blyton a run for her money. Like Blyton, he wrote adventure stories for children, but his were more sophisticated tales based on real places. I first came across Saville’s early Lone Pine books, set in the Long Mynd area of Shropshire, such as Wings over Witchend. I loved the fact they were based on real places (especially as my Aunty Jean came from Shopshire) and quickly moved on to the books set in Rye and Romney Marsh. I was intrigued by the strange landscape of the marsh described by Saville, but it took me 50 years to explore it for myself on this cycle tour.

I was staying at Rye’s Hope Anchor hotel, on which Saville based the Gay Dolphin hotel in his Rye stories. Saville died in 1982, but the Malcolm Saville Society keeps his memory and literary legacy alive, and unveiled a plaque at the Hope Anchor in 2023, seen above. I read part of the Gay Dolphin Adventure sitting outside the hotel that inspired Saville. It proved a fine base, and the staff were so helpful, retrieving my bike from safe storage despite the breakfast rush.

Getting off scot-free

One of the glories of language is discovering the forgotten meanings behind everyday expressions. Take ‘getting off scot-free’. My trip to Rye revealed that a scot was a tax – it has nothing to do with Scotland. In medieval times, a scot was levied on the citizens of flood-prone places like Rye. People who lived on higher, drier ground didn’t have to pay this scot – so were said to be getting off scot-free.

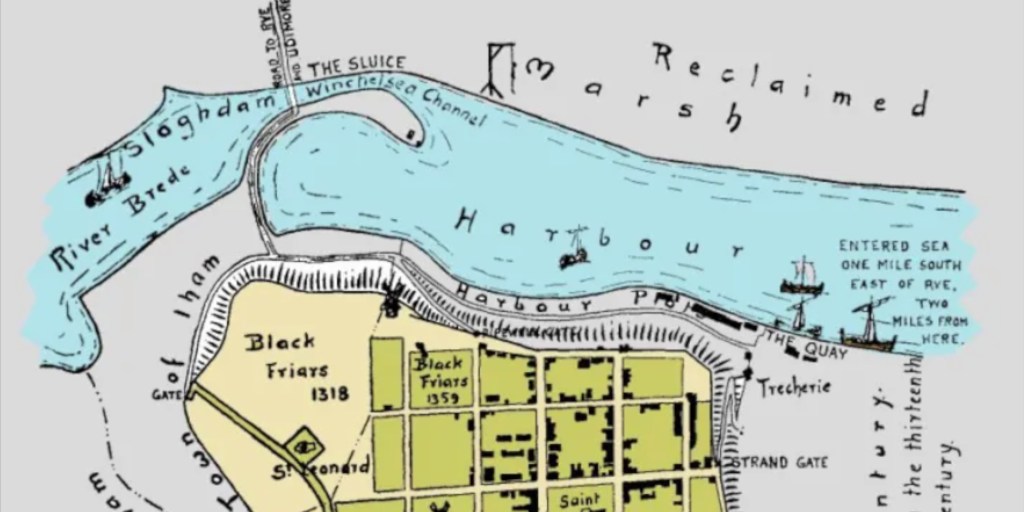

The lost city of Winchelsea

Some towns are cursed by fate. Take Winchelsea. It was, like Rye, one of the famed Cinque Ports, and a maritime jewel in medieval England’s crown. But this shingle coastline was vulnerable to the sea, and Winchelsea was battered into oblivion by a series of devastating storms in the 13th century. The final blow came in another great storm in 1287, prompting King Edward I to grant a charter for a new town of Winchelsea further inland but with a river harbour.

Matthew Green tells Winchelsea’s story well in Shadowlands, his book about Britain’s lost communities. Ironically the fates were just as cruel to new Winchelsea. The sea that had destroyed the old town retreated from its replacement, leaving this once thriving port high and dry. It’s just village today – a lovely village, but just a village. I’d like to spend time exploring it.

Reflections

I enjoyed Jack Thurston’s Lost Lanes tour of Romney Marsh and Rye, and will certainly follow more of his routes in the years to come. For me, the cycling on tours like this is almost incidental compared with the glory of the landscape and the history that clings to the places en route.

That was very interesting, thank you. I liked my own visit to Rye & Romney very much. Inspired by the Mapp and Lucia 2014 BBC television comedy drama based on EF Benson’s novels about the rivalry between two women in the town in the 1920s, we visited the various locations including Benson’s Rye house.

I was lucky enough to go up to the top of the town’s St Mary’s tower; it just so happened that it was an ‘open day’ when I went. Of course being the occasional ‘hobnobber’, I accompanied a Zimbabwean bishop to the top.

What a great story! That comedy drama passed me by. Shame it’s not on iPlayer! I’ll definitely return to Rye as there’s so much more to see.

I will tell you the story of helping arrest someone at St Pancras station.

Ancestors, by marriage, of yours lived just round the corner from St Pancras station in the early 1900s in the now redeveloped Pancras Square.

No mention of the Romney Hythe and Dymchurch Light railway?

Are you sure Winchelsea was one of cinque ports? I believe it was more properly one of the Ancient Towns (as an addition to the cinque ports).