Cycling journalist Ned Boulting’s latest book, 1923, is the story of how the purchase of the fragment of a newsreel report about a century-ago edition of the Tour de France led to an obsession with the forgotten rider seen on the film crossing a spectacular bridge. But this is far more than just another cycling book. It tells the story of a Europe still riven by tension and hatred five years after the Armistice.

The story begins when a friend pointed him to an item for sale in an online auction:

Lot 212. A Rare Film Reel from the Tour de France in the 1930s? Condition unknown.”

Ned bought the film for £120, and began a fascinating journey (literally and metaphorically) of discovery. The question mark over the date in the auction house listing was appropriate. The film, just over two minutes long, actually featured the 1923 Tour de France. Boulting found that the early Tours after the Great War followed exactly the same route, so he resorted to reading old newspaper articles, and even searching for weather reports, to establish that the stage from Brest to Les Sables d’Olonne featured in the film took place on 30 June 1923.

That £120 purchase could have had disastrous consequences. The company that made Boulting a digital video out of the ancient reel told him that the original was a nitrate film, and so highly flammable. Ned didn’t admit to the film restorers that the item had sat next to the radiator of his house after popping through his letterbox after he won the auction. If you happen to have a very old film reel at home, do check that it isn’t nitrate…

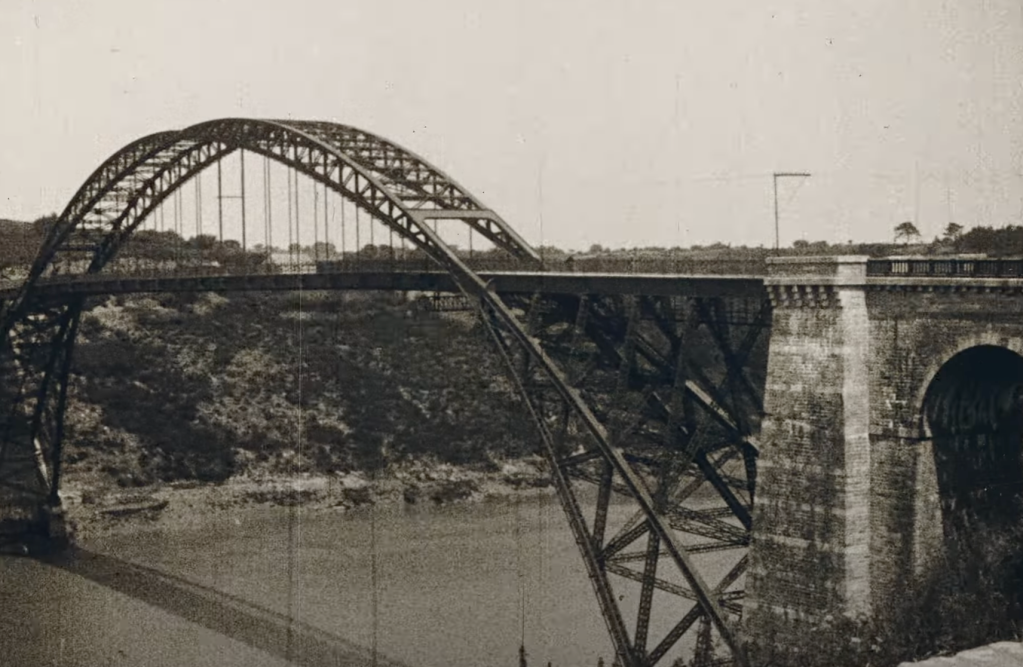

This is one of the defining images from the 1923 story. It shows the hero of the book, Théophile Beeckman, racing ahead on the bridge across the river Vilaine at La Roche-Bernard. As the subtitle of the book, The Mystery of Lot 212 and a Tour de France Obsession, suggests, Boulting became obsessed with uncovering the story of Beeckman, a man so obscure that he has all but vanished from the records. (As Ned discovered, there was virtually nothing about the rider online until he published 1923.)

But 1923 is far more than a book about a long-ago bike race. It is at least in part a biography of a year. I studied post-1918 European history for my 1982 A level history exam, but learned a lot of new details from Ned Boulting about the violent tensions between Weimar Germany and its neighbours. I knew all about the French occupation of the Ruhr in 1923 but until I read 1923 I had no idea that Belgian troops took part in the occupation. Boulting recounts how eight Belgian soldiers were killed when the train taking them back to Belgium was bombed as it crossed the Rhine, on the very day of the Tour de France stage that features in his film, 30 June.

Some of Boulting’s diversions from the topic of the 1923 Tour are more tenuous. We’re told of the premiere in Paris in 1896 of a play called Ubu Roi (King Ubu), which inspired the Dada movement. The tenuous justification for including this artistic moment was that it happened a month after Théo Beeckman was born, and that its drunken creator loved his bicycle. The composer involved in Ubu Roi happened to have died the day Beeckman was filmed crossing the bridge at La Roche-Bernard.

Another aspect of the book that I found less convincing was Ned’s imagined quotes from his hero Théo Beeckman. These are obviously intended to make up for the almost complete lack of any surviving accounts from the rider himself – not a problem a biographer of today’s cycling stars would experience.

By contrast, I was delighted by the account of how Beeckman and three other riders spent the rest day on 1 July 1923 racing donkeys and children’s bikes on the beach at Les Sables d’Olonne. The fun was witnessed by a small crowd, and immortalised in a photo report in Les Miroir des Sports. I was also enchanted by the tale of the Tour rider Maurice Guénot stopping to milk a cow to slake his thirst. What a world away from today’s professional cycling scene.

Credit: postcards featured on Bridgemeister

The old bridge at La Roche-Bernard no longer exists. As 1923 explains, it was destroyed in 1944 when lightning detonated demolition explosives, placed by the Germans to prevent Allied liberation troops from crossing it. It has been replaced by a less elegant suspension bridge. The original 1839 bridge that crossed the Vilaine here was even more spectacular, and looked like a clone of Telford’s beautiful 1826 Menai Bridge. The arch bridge used the original piers and approach viaducts, which now stand abandoned.

The most tragic character in the book was the winner of the 1923 Tour, Henri Pélissier. He was described as being incapable of happiness, and his violence and affairs drove his wife to suicide using Henri’s pistol. Three years later, his lover shot him dead with that same gun, moments after he scarred her daughter with a knife in a crazed, drunken rampage. As the judge who gave her a suspended prison sentence commented, ‘He was one of the great glories of French cycling. But he had a character that was irascible, violent and perverse’.

Reading 1923 reminded me of one of my favourite books and television series from my teenage years, Connections by James Burke. As the title suggests, it showed how inventions and other technological developments are so often linked. For example, Burke explained how the application of tar to coat wooden ships and so protect them from the destructive naval ship worm led to the use of coal to produce gas for lighting, transforming urban and domestic life. In time Scotland’s Charles Macintosh used the coal tar waste to dissolve rubber and so produce the Mackintosh coat. Later still, tar was used to create the first artificial dye. Burke took the story further by showing the connection to the production of fertiliser and the gun cotton-based explosives that sustained Germany’s war effort during the Great War.

Just a five years after the end of that war to end all wars, the fifth postwar Tour de France was captured on film. There’s something magical about watching moving pictures. Ned Boulting believes his 1923 film features the only surviving moving images of the founder of the Tour de France, Henri Desgrange. It’s a fragment of history, seen by thousands in 1923 on the Pathé cinema newsreel and then lost for generations before being rediscovered by Ned Boulting.

Here’s the film that inspired Ned’s Tour de France obsession.