This is a bleak midwinter for Keir Starmer’s Labour government. Elected by a landslide just six months ago, Labour is sinking fast in the polls, and the modest enthusiasm that greeted its election has long since disappeared. Strategic messaging and policy mistakes have led to despair amongst many supporters, and jubilation from the populist insurgent party, Reform UK, now neck and neck with Labour in the polls.

True, at least some of the backlash is the traditional reaction to a Labour government from Britain’s dominant right wing press. All too often the BBC falls for the mistaken view that it has to amplify every right wing criticism of Labour. And people tend to be more fickle these days – a trend that benefitted Labour as it went from its worst election defeat for 84 years in 2019 to a landslide victory last year. But most observers accept that Labour has made an exceptionally poor start, even allowing for its dreadful inheritance.

Lessons from Thatcher’s experience

Labour’s collapse in support and morale so soon after being elected is very unusual, especially for a party winning power from opposition. The only comparable example, ironically, is an encouraging precedent for Labour. Margaret Thatcher has now passed into legend as the iron lady: indomitable, unyielding and triumphant, at least until hubris took over after her third election win in 1987. The reality is more interesting.

In the autumn of 1981, Margaret Thatcher was under siege. Just over two years into her premiership, her monetarist economic policy (trying to reduce inflation by controlling the amount of money in the economy) had proved disastrous. Having condemned Labour for presiding over rising unemployment (‘Labour isn’t working’ in the words of an infamous poster) and inflation, the Thatcher government’s policies contributed to far more job losses. In her first three years, Britain lost a quarter of its manufacturing capacity. The nightly news bulletins were dominated by reports of yet more famous brands laying off staff, or going bankrupt.

The cause in many cases was the soaring value of the pound, caused by high interest rates, which made our exports hugely expensive. (In late 1979, chancellor of the exchequer Geoffrey Howe raised interest rates to a crippling 17 percent largely because investors were not willing to lend money to the government – the so-called gilt strike, which shows that the gilts (government bonds) crisis that did for Liz Truss had an unexpected precedent in her heroine’s traumatic early years.)

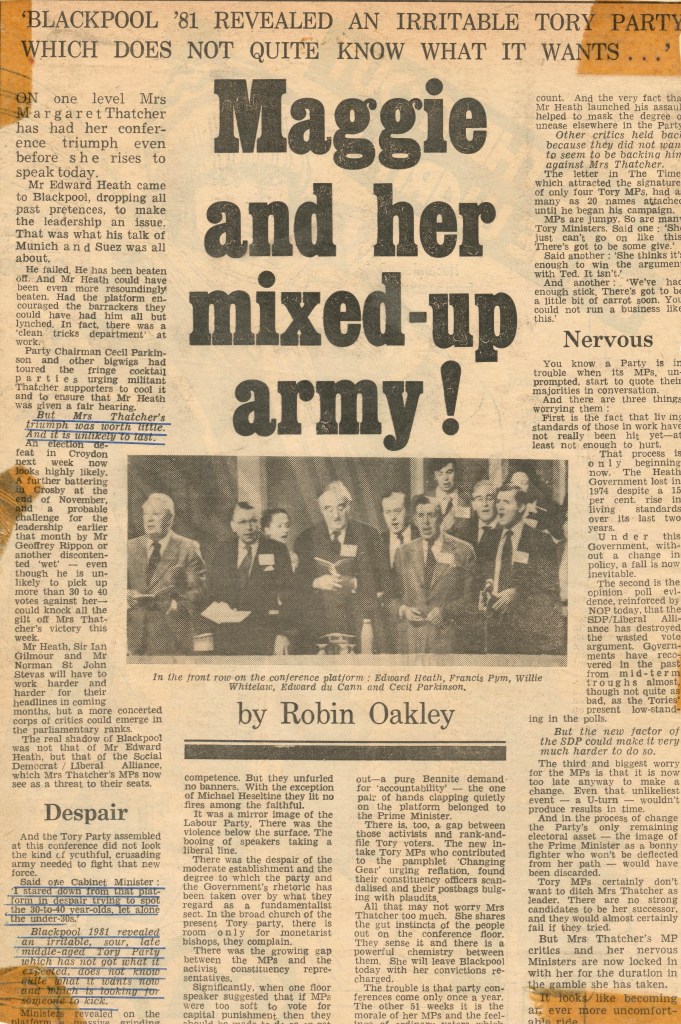

Above: the Tory-supporting Daily Mail reveals the troubled state of Thatcher’s party, 1981

Thatcher maintained a public image of defiant confidence in the face of the onslaught. At a time when one job was lost every thirty seconds, she famously told the 1980 Conservative party conference, ‘The lady’s not for turning!’, a pun on the title of the 1948 play, The Lady’s Not for Burning. She insisted that There Is No Alternative (TINA) to her approach. But she was rattled and under huge strain. Her party was third in a Gallup opinion poll (at 23 percent) with the new SDP/Liberal Alliance at a staggering 50 percent. (The Social Democratic Party was a breakaway from a Labour Party now turning sharply left.) Her natural tendency to hector and bully became more pronounced, and she regularly abused her loyal chancellor in front of officials. Even mild-mannered Howe (who later helped destroy her premiership in 1990) was angered by her endless abuse, according to future chancellor Nigel Lawson.

Most commentators agreed the value of the pound needed to fall to allow any chance of economic recovery. That meant interest rates needed to be cut. But after that gilt strike of 1979, rates could only be cut if public spending was slashed – hence the savage 1981 budget, which led to a famous letter to The Times in which 364 economists criticised the government’s economic policy. Even the Tory-supporting Express screamed: You name it, he’s taxed it.

But it is a myth that Margaret Thatcher was completely unyielding. She was a far more flexible premier at times than less skilful Tory successors like Cameron and Truss. In February 1981, she caved in to the miners. The state-owned National Coal Board announced the closure of 23 pits, prompting the NUM miners union to threaten a national strike. On being told that Britain didn’t have sufficient stockpiles of coal to endure a length strike, Thatcher ordered a u-turn, which delighted Ted Heath, whose premiership was destroyed by the miners. (Three years later, she was better prepared for a year-long strike that marked the beginning of the end of coal mining in Britain.)

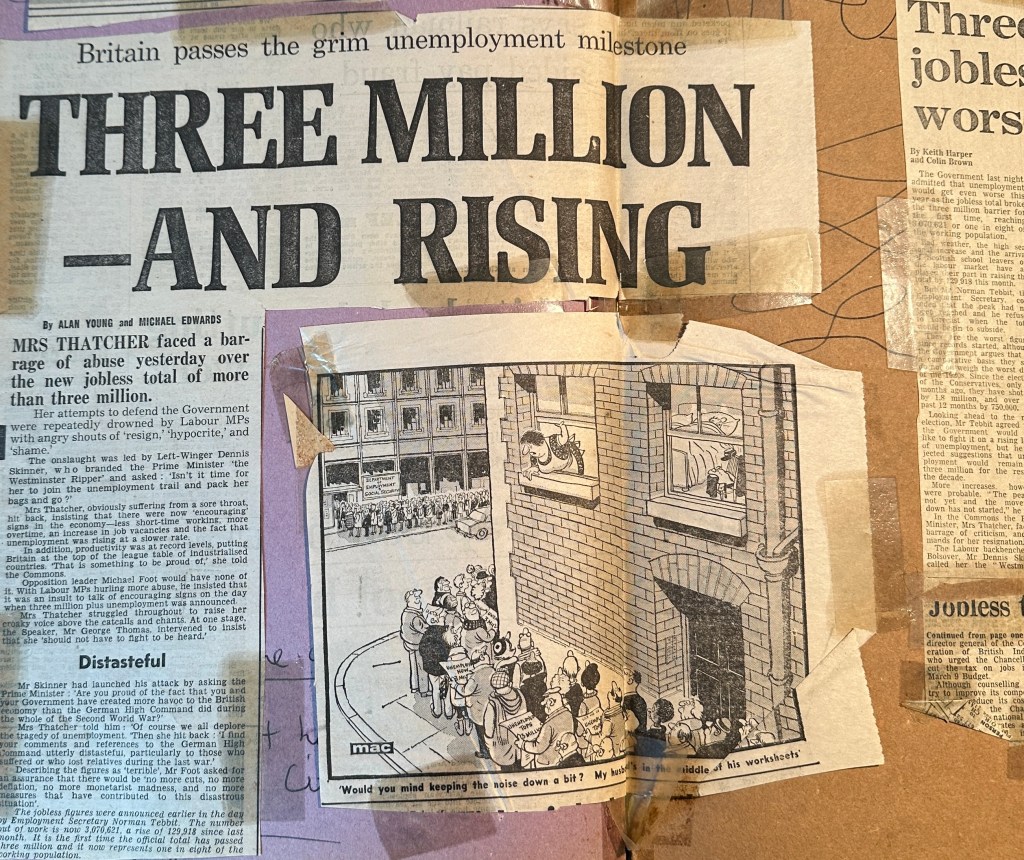

In January 1982, Britain passed a terrible milestone: three million people were officially out of work, for the first time since the 1930s. While state support for the jobless was more generous than between the wars, the loss of work was a devastating blow, especially in places like my native South Wales, Scotland and the north of England. Although Margaret Thatcher wasn’t the only reason (many already-failing companies went under) it was estimated that 75 percent of the job losses were caused by her policies.

Did Argentina’s murderous junta save Margaret Thatcher’s premiership?

After three grim years, Margaret Thatcher’s premiership seemed doomed. On 2 April 1982, Britain suffered the humiliation of the invasion of one of its few remaining colonies, the Falkland Islands in the South Atlantic. Argentina had long claimed the islands, despite the opposition of the 1,800 residents, and its brutal military dictatorship seized the territory in a desperate attempt to appease its unhappy, oppressed citizens.

Against all the odds, Britain’s armed forces sailed 8,000 miles to reclaim the islands, as I recalled on the 40th anniversary of this bizarre episode in Britain’s post war history. Many people are convinced that the Falklands war saved Margaret Thatcher. It’s certainly true that she could not have survived defeat – the national mood on the night of 2 April was utter shock, and the iron lady was far from confident during the emergency Saturday House of Commons debate the following day. Yet had Argentina never invaded, there’s a strong case that Thatcher’s government was over the worst of its crisis, despite those shocking unemployment figures just three months earlier. This is where the Thatcher precedent offers hope to Keir Starmer’s embattled Labour administration.

Even before the first Argentinian solder stepped onto the Falklands, the Conservative political recovery was under way. While its support was languishing at 23 percent in late 1981, by the spring it had risen to 31 percent. Thatcher’s own approval rating climbed from 18 percent in December 1981 to 30 percent the following month. A combination of falling interest rates and rising consumer spending meant the economy was on the rebound, despite record jobless figures. (The brutal story of the 1980s is that the 90 percent of people who kept their jobs became steadily better off.) Dominic Sandbrook argues in his brilliant history, Who Dares Wins: Britain 1979-1982, that if the war made a difference it was to accelerate a recovery that was already under way. Sandbrook cites the academic paper Government Popularity and the Falklands War: a Reassessment, 1987, in the British Journal of Political Science, which estimates that the war boosted Conservative support by at most three percentage points for no more than three months.

This seems fair. The Labour party was bitterly split between a rampant left wing, under Tony Benn, and the traditional right, in retreat after the failures of the Callaghan government. Its improbably leader, Michael Foot, was a romantic left winger more at home writing about Swift and Hazlitt than he was leading a 20th century political party. (The journalist Peter Riddell once saved him from stepping in front of traffic. ‘Oh, thank you! I was thinking about Hazlitt’ Foot replied.) It seems improbably that Foot could ever have won against Thatcher.

Meanwhile, the SDP Liberal Alliance was fading from its high water mark in late 1981, and Roy Jenkins’ stunning win in the Glasgow Hillhead by election was the last hurrah, although it did come agonisingly close to beating Labour to second place in the 1983 general election. Thanks to Britain’s first past the post electoral system, it gained just a fraction of Labour’s seats.

The true Falklands factor

Where the Falklands win did make a dramatic difference was how Britain regarded itself – and its now imperious leader. The country had endured a grim 12 years under Tory and Labour governments. Much as today’s Britain feels like a place where nothing is going right, so it was in 1982. Yet the extraordinary feat of arms of reclaiming the Falklands gave many people a boost, in the same way that a sporting triumph raises the mood. Suddenly, the memory of the humiliation of Suez in 1956 was replaced with a triumphant one. The enormous crowds that greeted the returning soldiers and marines on requisitioned cruise liners Canberra and Queen Elizabeth II were evidence of mood of community celebration.

Not everyone shared this triumphant mood. Hundreds of young British and Argentinian men had died, and others such as Simon Weston from South Wales suffered life changing injuries. Some criticised the British response as a colonial action, out of place in the late 20th century. I myself in my 1982 diary noted, ‘The lull after the initial storm in this, Britain’s last colonial war’. Yet the description is misleading. The 1,800 residents of the Falklands wanted to remain under British rule, not that of a brutal Argentinian dictatorship that attached electrodes to the genitals of its opponents and threw them out of aircraft to their deaths. Britain was fighting to uphold their right of self determination.

The Falklands war carried certain echoes of the second world war, reinforcing a legend of plucky Britain standing firm against brutal foreign forces. Watching rare film of Harrier jump jets tearing off a storm-lashed aircraft carrier into the mist evoked memories of Spitfires and Hurricanes defending our own islands in 1940. For a nation still obsessed by the myth of 1940, it was heady stuff.

It’s worth noting that Thatcher raised her game as a war leader. She realised that she knew nothing of military matters, and listened to her military advisers and commanders. The hectoring and lecturing were put aside for the duration.

Lessons for Keir Starmer

As we have seen, Margaret Thatcher was under siege for much of her first three years in power. Yet she survived, and was enjoying recovering poll and popularity ratings even before General Galtieri ordered the Falklands invasion. If Labour’s policies do start to raise living standards and improve public services, it is entirely possible that Starmer’s torrid first six months will be forgotten.

But, like Thatcher in the Falklands war, Starmer needs to raise his game. He must become a political teacher and communicator. He and his team urgently need a compelling story to justify and explain its mission. And find some energy and passion! As I blogged last autumn (Blaming the Tories isn’t enough):

Starmer and team were understandably paranoid about losing the election. But they must now move beyond the doom-laden narrative of the government’s first two months to set a positive, optimistic vision for the next five years. This has to be done quickly. Starmer must avoid becoming another Theresa May: her utter inability to communicate let alone explain to the nation and her party what she was trying to achieve doomed her premiership especially after the catastrophic result (for her) of the 2017 general election. As Steve Richards put it, ‘She not only failed to tell her story, but did not even make an attempt. This was her fatal flaw – not only a failure to communicate, but an indifference to the art’. (The Prime Ministers: reflections on leadership from Wilson to Johnson, 2019)

Labour did have a terrible inheritance. But it has scored too many own goals. For a government pledged to economic growth to increase taxes on employment was utterly stupid. If it is to emulate Thatcher and bounce back to victory in 2028 or 2029 it will have to prove far better at strategy, policy – and politics.

Afternote

The dog-earned newspaper cuttings featured in this post are from a scrapbook I kept from 1975 until 1982. The earliest stories were about football, as I followed the fluctuating fortunes of Cardiff City Football Club. Later, I kept cuttings about the transformation of Rhodesia into Zimbabwe, the challenges of the Thatcher government and the Falklands war.

Pingback: Headlines from my 50 year old childhood scrapbook | Ertblog

Pingback: Thatcher’s thunderbolt: becoming Tory leader, 50 years ago | Ertblog