This was the forbidding opening title scene in the BBC’s iconic 1970s television drama, Colditz, with the outline of Colditz Castle – the notorious second world war prisoner of war (PoW) camp, Offlag IV-C.

Back in the seventies, Colditz was amazingly prominent in British minds, 30 years after the war. The television series ran for two years, based in part on the bestselling books by Pat Reid, one of the first British prisoners to make a ‘home run’ to Britain. (As Nazi Germany controlled most of Europe, getting out of Colditz was just the start of a successful escape.) It was the most successful television drama the BBC had ever made, watched by a third of the viewing public. Most of the prisoners behind the walls of Colditz Castle had already escaped from other German prisoner of war camps, and so were an elite band of escapologists.

I’d barely given Colditz a thought for decades, but that all changed when I read Ben Macintyre’s 2022 book, Colditz, Prisoners of the Castle. Macintyre is a wonderful storyteller, with a knack of uncovering a multitude of spellbinding anecdotes and tales about even familiar topics. My childhood Colditz memories were replaying in my mind as I read his account of the wartime fortress prison.

All the familiar British names feature: Pat Reid, Airey Neave and Douglas Bader. I was amazed to learn that the Germans gave safe passage to an RAF bomber that parachuted a prosthetic leg onto a Lufftwaffe base in occupied France to replace one that Douglas Bader had lost after being shot down and captured. (Bader lost both his original legs in a flying accident in 1931.)

I was intrigued by the tales of the French escape attempts – especially Pierre Mairesse-Lebrun, who rode a bike along a German autobahn (motorway) bare-chested as convoys of German troops headed the other way towards the eastern front as Germany invaded the Soviet Union. Despite this conspicuous act, he made it over the Swiss border.

One of the saddest and most shameful episodes is the experience of the Indian doctor Birendranath Mazumdar. He was a dedicated Indian nationalist, keen to see the end of the British Raj. Yet this admirable man joined the British army as a doctor on the outbreak of war, viewing the defeat of the Nazis as the priority. Despite being given repeated opportunities by the Germans to win his freedom, he insisted that he had sworn allegiance to King George VI when joining the army, and would not switch sides. Shamefully, he was treated with suspicion and prejudice by the British officers, a scandal that endured to the end of the war.

The word hero is grossly overused, but several people featured in Mcintyre’s book truly deserve the epithet. A 66 year old woman in Warsaw risked torture and death at the hands of the Gestapo by running an escape network for fugitive British prisoners of war. She lived her precarious existence as Mrs Janina Markowska, but was actually born in Scotland as Jane Walker in 1874. Rudolf Denzler was a Swiss official tasked with ensuring that the Germans respected their prisoners’ rights under the Geneva Convention, visiting PoW prisons as a representative of the ‘protecting power’, Switzerland.

As Colditz was run by the regular German armed forces, the Wehrmacht, its prisoners were generally treated well, and for much of the war were actually better fed than their jailers, thanks to regular food parcels from the Red Cross. But one group of PoWs was at grave risk as the Nazi regime collapsed. The so-called prominente were VIP prisoners, including Churchill’s nephew Giles Romilly, held as bargaining chips. They were moved out of Colditz by the murderous SS just before American troops arrived, and the brave Swiss man Denzler followed them in his own car in the hope of ensuring no harm befell them. He visited the home of Nazi Germany’s foreign minister to warn Ribbentrop of the threat to the prisoners, and lobbied other German military officers. Happily, his mission was successful.

The other person who shines through Macintyre’s book as a force for good against evil is Reinhold Eggers. Eggers was the security officer at Colditz, charged with preventing escapes. Macintyre compares Eggers with an old fashioned Prussian schoolteacher, with a very correct manner, little humour and a determination that prisoners should not be mistreated. He had spent time in Cheltenham before the war, and was puzzled why the British officers didn’t behave like the people he’d got to know in that formal Gloucestershire town. He supported Colditz commandant Gerhard Prawitt’s decision to hand control of the castle to the prisoners as the Americans raced towards it, while desperately keeping the fact from the SS. Unlike many Colditz officers he stayed in the east at the end of the war, not expecting the Russians to inflict 10 brutal years in a concentration camp. After being released in 1955, he moved to West Germany and became friends with several of his former Colditz prisoners. When Pat Reid was the subject of ITV’s This is Your Life show in 1973, Eggers was a surprise guest.

My Colditz memories

As a child in the 1970s, I was very familiar with the Colditz story. I read Pat Reid’s books avidly and rereading the Latter Days at Colditz this week vividly remembered reading as a child Reid’s quote from a former German officer at Colditz: ‘Such a collection of enfants terribles as yourselves could not be handled with kid gloves…’ (This was the first time I’d come across the phrase kid gloves.) Half a century ago, Pat Read’s books taught me that Colditz escapers dreaded the city of Ulm, as a number of them had been caught there. Mcintyre brought this back to me, recounting how Airey Neave and his Dutch fellow escaper Tony Luteyn almost came to grief because of a suspicious woman in the railway ticket office who tipped off the railway police. Neave and Luteyn evaded an armed policeman through an Ulm coal store, and made it to neutral Switzerland.

This was one of my Christmas presents in 1974: the Escape from Colditz board game, which is still available today. The ubiquitous Pat Reid helped Gibson Games create the game, which I enjoyed playing with my primary school friends over the holidays.

The Colditz glider

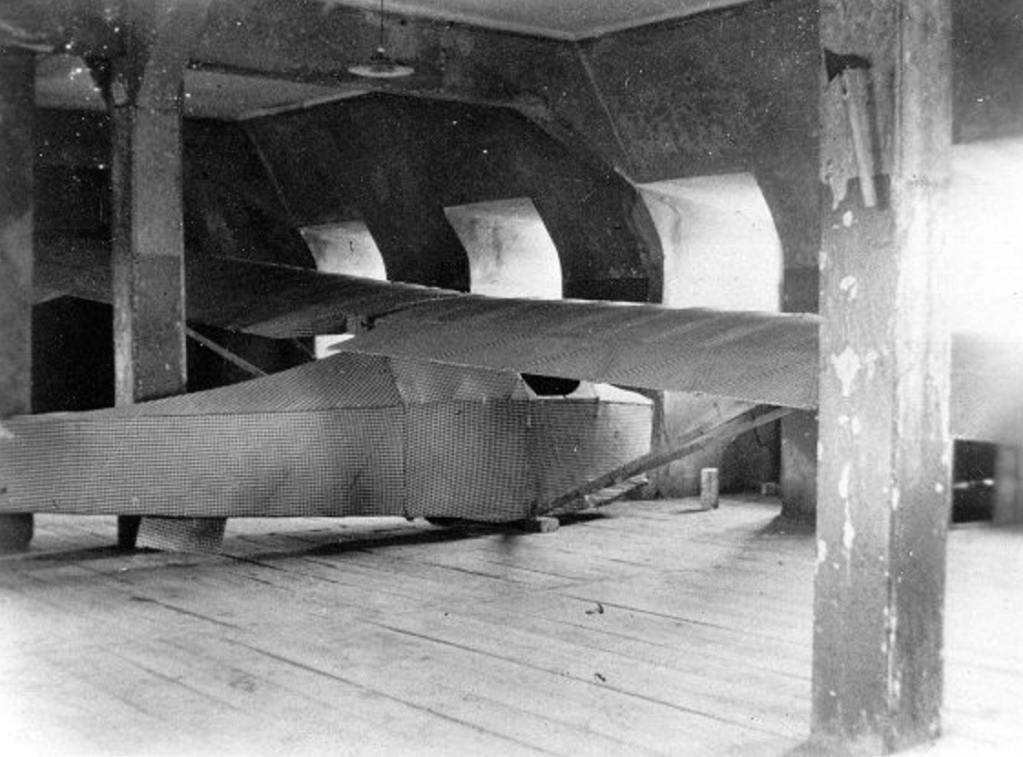

Most escape attempts featured tunnels or impersonations of German officers. But in the final months of the war, British prisoners hatched an audacious plan to fly out of the castle. In the attic, they built a glider using floor boards, bed slats and other materials from the fortress. They designed it following the principles outlined in a book they found in the prison library: Aircraft Design by Cecil Latimer Needham. (The Germans never suspected this volume could be an escaper’s manual.) To minimise the chance of detection, they built a false wall across the attic. The guards never noticed that the remaining attic space was now seven feet shorter. To enable the glider to take off, the British officers built a 600 feet launch track to be placed on the roof at the moment of truth.

As Mcintyre says, the glider never flew, and its fate remains unknown. Its makers left Colditz as free men in 1945, rather than as desperate and probably doomed pilots. In 2012, a full scale remote control replica was launched from the castle roof and landed safely on the meadow across the river.

Back in the seventies, I was thrilled to see a replica of the glider hanging from a gallery ceiling in the Imperial War Museum in London. It featured in a wildly popular 1974 Colditz exhibition, capitalising on the interest in the final series of the BBC drama. The replica had been built for the television series, and may still exist in IWM storage at Duxford.

Visiting Colditz

Back in 1974, Colditz was virtually out of reach for British visitors, miles behind the Iron Curtain in communist East Germany. (The ironically named German Democratic Republic.) I remember learning as a child that it was located in the triangle of three cities: Leipzig, Dresden and Karl Marx Stadt. (Since the fall of the Berlin Wall, the latter has adopted its historic name, Chemnitz.)

The end of communism has made Colditz a tourist attraction, with a small museum dedicated to its wartime role. It would be fascinating to make the journey one day, and to see in real life the features once so familiar through the BBC series, board game and books.