It was one of my strangest dreams. I was in a chip shop in the Rhondda Fach in South Wales in 1985, watching miners’ leader Arthur Scargill sadly announce it was all over. The year-long battle to stop the mass closure of Britain’s coal mines had ended in defeat.

The dream was just that. But it reflected the painful reality of that March day in 1985. The miners of Maerdy in the Rhondda Fach marched proudly back to work, but we all knew that the Thatcher government had won a bitter struggle.

The strike began forty years ago on 6 March 1984, after the National Coal Board announced that 20 mines would close, with the loss of 20,000 jobs. Scargill said that the government would close far more mines (ultimately he was proved right in the years after the strike ended).

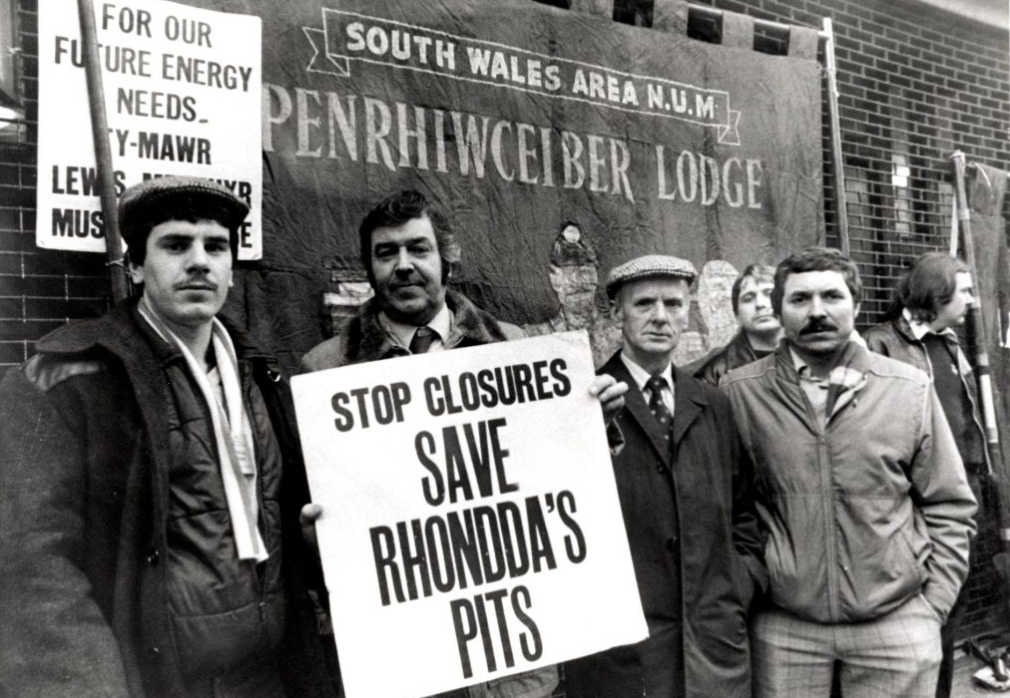

The battle that followed was Britain’s last great industrial confrontation, which left many of us with deeply conflicting emotions. The British people had long admired the miners, enduring one of the hardest and most dangerous ways to earn a living. (I blogged about some of the tragedies that struck South Wales in this blogpost.) They also sympathised with colliery communities such as Penrhiwceiber and Maerdy. These isolated villages existed to serve the coal trade, and faced a bleak future if Thatcher axed the coal industry. The women of those communities were magnificent in the grim months of 1984 and beyond, fighting for justice and speaking with eloquence.

But the National Union of Mineworkers’ refusal to ballot its members for strike action seemed cynical and manipulative, and split the anti-strike miners of Nottinghamshire against the NUM. The violence seen on the picket lines and treatment of working miners sickened many – though Thatcher’s talk of the enemy within was equally repulsive, along with the prime minister’s use of police brutality to crush the strikers.

Going on strike in March, at the end of the winter, hugely reduced the impact of the walkout, especially as the Thatcher government had learned from past mistakes and ensured that Britain’s power stations had enough fuel to last for the duration. (I remember seeing a mountain of coal at Didcot power station when passing on a train.) Back in 1981 Thatcher had pragmatically conceded to the miners when she realised the government was ill-prepared, as illustrated by the classic Private Eye cover, above.

Feelings ran high on both sides, and sometimes spilled over into sickening violence. The battle of Orgreave in the hot summer of 1984 became infamous, as police and pickets fought what resembled a medieval battle at the Orgreave coking plant in Yorkshire. The authorities were determined to teach the miners a lesson, and avoid a repeat of the miners’ victory at Saltley Gate in Birmingham during an earlier strike in 1972. The police tactics – including mounted charges against the pickets, and brutal beatings of defenceless miners lying on the ground – were roundly condemned at the time. The South Yorkshire Police later paid compensation to many of the miners involved – but went on to behave even more notoriously during and after the Hillsborough disaster in1989.

Worse was to come. In November 1984 a taxi driver, Derek Wilkie, was killed when two thugs, Dean Hancock and Russell Shankland, threw a concrete block onto his cab from a bridge over the heads of the valleys road as he was taking a working miner to Merthyr Vale colliery in South Wales. They were convicted of murder but the sentence was reduced to manslaughter on appeal. The horrific killing reduced support for the miners in the closing months of the strike. The irony is that the miner Wilkie was taking to work was one of just a handful in South Wales who had chosen to go back to work. The police escort did nothing to save Wilkie from Hancock and Shankland’s callous disregard for human life. They were lucky to spend just four years in prison.

The bitter dispute was a cruel challenge to new Labour leader Neil Kinnock, who had taken over just months before the strike began. He came from a mining family and represented a constituency deep within the South Wales coalfield, Bedwellty. Kinnock immediately recognised the terrible dilemma: he naturally sympathised with the miners, but saw Scargill’s refusal to hold a strike and the violence on the picket lines as toxic. He tried to strike a balance, but the right wing London media were never going to give a fair hearing to him or the miners.

Forty years on, not a single deep coal mine survives in Britain. (The last, Kellingley in Yorkshire, closed in 2015.) But you can still go down a coal mine. Big Pit National Coal Museum at Blaenavon, South Wales, is one of a handful of old collieries that have become tourist attractions, showing what life was like for the men who kept the home fires burning for generations.